Let’s Get Caught Up, Continued

The night I wrote the last blog post, a call from my father interrupted me. He screamed in agony into the phone that something horrible had happened…

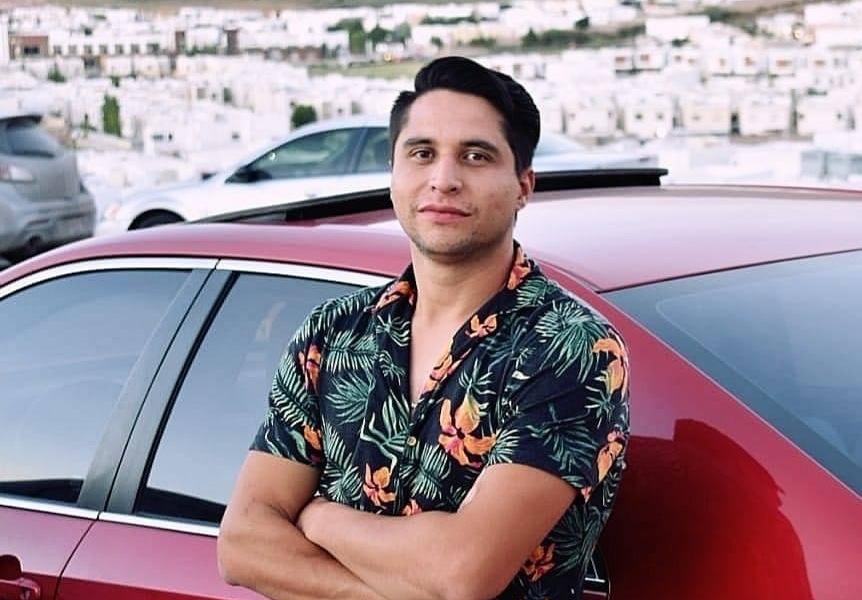

… I met Andrés when he was eight years old. My father was dating his mother, and Andrés latched on to my dad as his own. Little by little, the kid became a permanent fixture around my dad’s shop. Like any other child in that little town in Mexico, he got in plenty of trouble. He preferred running around and playing instead of school, but he showed how smart he was by how quickly he grasped the concepts dad taught him. Like dad did with me, he poured his entire knowledge of machines into Andrés.

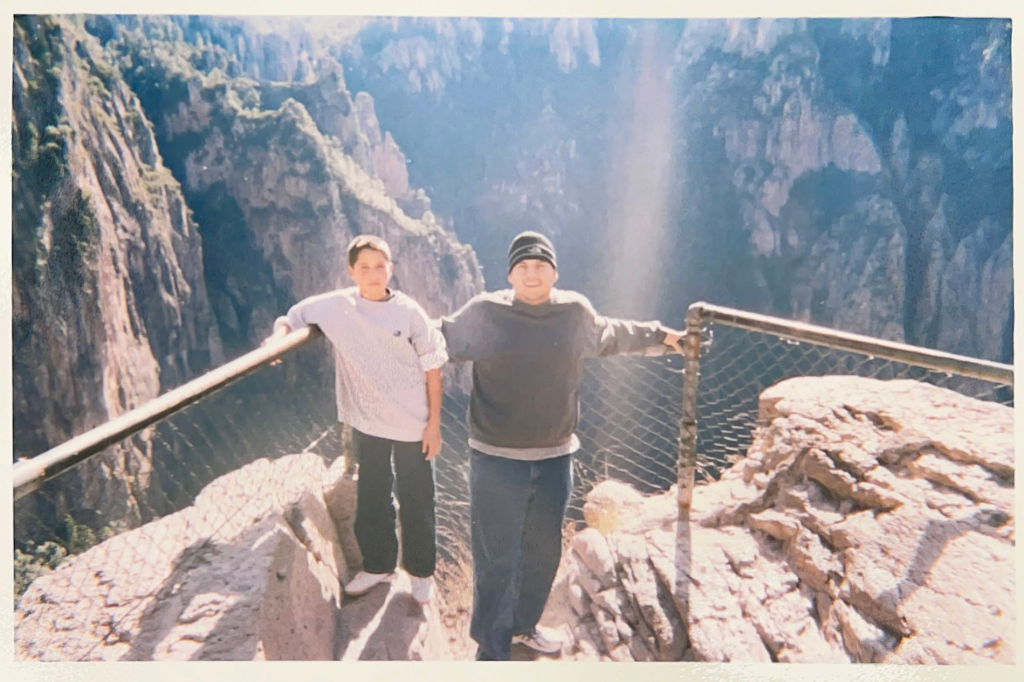

Every time I visited dad, Andrés would beg and plead with his mom to let her go to our little town and hang out with us. We would get into the car and drive off into the mountains, going to the waterfalls, the rivers. My other brother would also join us. Slowly but surely, we became family. We called each other “brother.”

I’m not going to lie to you. It wasn’t easy to accept him into the family. He came into our lives at a time when things were strained between dad and I, so I saw Andrés as dad’s attempt to replace me. Nothing could be further from the truth. He was not replacing me. He was adding to our family. Dad did what he did with me and my other brother. He took another young man under his wing and did his best to teach him about life and how things are supposed to be. For all his faults, dad is an okay guy.

Last year, as the pandemic slowed down just a little between the Alpha and Delta waves, I traveled to Mexico to check on dad. Andrés had joined the state police, first as a forensic scientist and then as an officer on patrol. He took time off from the job to spend a few days with dad and I. We traveled to a canyon, ate Mexican food from a roadside stand, and just chatted the day away. He told us how much he loved his job, and how he felt like he was doing something good in the world.

Later in the year, a group of Central American immigrants were kidnapped by a criminal group near the border with Texas. Andrés and his team were the first to get to the warehouse that housed well over a hundred men, women, and children. He said the conditions were deplorable, and many people suffered from dehydration and diarrhea. The criminals held them there for ransom, calling their relatives in the United States and not releasing the kidnapped people until a hefty ransom was paid. Many people were not released. Some died in the warehouse. Some were found in the desert, killed in cold blood even after a ransom was paid.

Andrés told me his unit was told not to go into the warehouse immediately, because it might be booby-trapped. He said they didn’t care and grabbed a ladder to jump over the fence. It affected him because he spent a few months as an undocumented immigrant in Texas, before returning home and going to a school of forensic sciences. He told me how lucky he was to not be in their position, or to put us through what their families went through.

His work with the police went from working with the forensic scientists to grabbing a weapon and heading out on patrol. He bulked up and grew up a lot, from when he was admitted into the force to when I saw him next. He was older, wiser. He wasn’t like the brazen, cocky young cops I’ve encountered so many times. He had nothing to prove, and all he wanted to do was do good in the world…

…Dad cried into the phone with a heartbreaking wail. “He’s dead,” he said between sobs.

“Who?” I asked, feeling my chest tightening, readying myself for whoever it was that died and broke dad’s heart so badly.

“Andrés,” he said. “Andrés is dead.”

I jumped on a plane on Monday morning. We left BWI Airport a little late because a flight attendant was delayed, and that would set up a whole series of events for the day to come. Instead of arriving in Chihuahua City in the evening on Monday, I would not arrive until the evening of Tuesday. The flight from Baltimore to Austin was delayed, then the pilot tried twice to land in Austin in a bad rainstorm. He went around twice and then diverted to Houston.

Once in Houston, a crew member said people going to El Paso (where I was going) could deplane. He said a direct flight from Houston to El Paso was about to leave, and we could jump on it. Well, by the time I got to that gate, the flight was already full. They asked me to return to the original plane and wait for it to leave for Austin again. After a few minutes back at the plane, they called me by name and said they had found another flight for me. The thing was, that flight was from Houston to Las Vegas, then I would catch another flight to El Paso, arriving around midnight. I didn’t care. I said I’d do it.

After an hour of waiting to be re-ticketed, the airline representative told me the flight to Vegas was now full. There were no other flights. I found a flight on another airline in Houston’s other airport, so I booked that flight and caught an expensive Uber ride over. Things were not better at that airport. The weather from Austin had drifted into Houston, and now no flights were landing or leaving Houston. The flight at two in the afternoon was delayed to four, then six, then eight. By nine that evening, we were told the plane to take us to El Paso had landed, but the crew for it were late on another flight… As a result, that flight was cancelled.

By then, I had been in communication with my dad, texting him updates as I went. I had also been texting and calling my wife. She talked me off the ledge several times as the travel ordeals piled up. I was feeling helpless and alone, and incredibly sad. When the flight was cancelled, I broke down crying in front of everyone, and I did not care. I cried and cried as I booked a hotel room for the night and another expensive Uber ride. I didn’t sleep a wink for the second night in a row.

Tuesday’s weather was far better. It was still cloudy, but there was no rain. Flights were leaving Houston with no problem. I jumped on a plane at noon local time, and I was in El Paso less than two hours later. When I got to the car rental place, they told me they had no cars to rent, but they did have a pick-up truck. I didn’t care. I took it, and I started the four-hour trip to Presidio, like I have done so many times in my life. Except that I did it — yet again — because of an emergency or tragedy.

The little town of Juan Aldama, in the mountains of Chihuahua, had always been a refuge for me. I grew up splitting my time between there and Ciudad Juarez, where I was born. Juarez was busy, hot and dry. It was ugly and gray. It was where I went to school, so I did not like it. Aldama was green, with the alameda lined with big oak trees planted by my grandfathers and their fathers. The weather was hot, yes. But it would cool down in the evenings, and the rainy season was fun because we got to play in the irrigation ditches and streams. It was a place that used to be safe for kids to be kids. (The wars between cartels has changed all that.)

Both my parents’ families lived in Aldama, though they had moved there from other regions of the country. It was close enough to the state capital (Chihuahua City) for people to work there and live comfortably in Aldama. It was also a center for raising and selling cattle and many agricultural products. As the years went by, some family members moved north to Juarez. Some moved across the border into Texas. But we all returned to Aldama… The joke is that if the world ends, we’ll all rally back at Aldama.

Traveling to Aldama from Juarez meant jumping on a bus or a relatives’ vehicle (or my own vehicle once I had one) and making the five-hour drive from Juarez to Aldama on a two-lane highway. You’d often be racing the buses and tractor trailers, driving by memorial markers on the side of the road where people died in car accidents.

Eventually, you’d arrive in Aldama and let the fun begin. My cousins were there. My friends were there. Summers were some of the best times I had. Christmas was also good, but just a bit cold with short days. There were no deadlines, no real work to be done. Our parents and grandparents took care of everything. Even in our young adult days, it was all about having fun and living without a care in the world. Aldama was our refuge.

“This seems very familiar,” my dad said. “Like I dreamed this would happen to Andrés.”

“It’s not that,” I replied. “It’s nine years to the day since my uncle…”

The weather gets hot during the day starting in April. At night, the temperatures can dip into the forties, but the temperature then rebounds quickly during the day. Sometimes, daytime temperatures can get into the nineties. It’s not too bad, though. There is no humidity to speak of. The sweat evaporates off of you quickly, cooling you off. You get a hell of a tan, though.

Back in 2013, when I was accepted into the “best public health school in the world,” I traveled to Aldama to celebrate with my dad. I had struggled the year before to get in, so we were all quite happy that I finally made it. The years ahead would be rough, but at least I was in. To add to the celebratory mood, one of my cousins had returned from the United States after several years of working there. His father — my uncle — was happy to see his oldest, just like my dad. My uncle threw the biggest party for him, and everyone was invited.

The party was great. There were mariachis, great food, and lots of alcohol. My uncle got sloshed, and his kids were all happy to be back together. Dad and I sat back and watched with joy how happy he was, especially after dad mentioned my uncle had been sad lately. The rest of the weekend was more catching up with everyone, sharing in my recent acceptance into the school of public health, and celebrating the return of my cousin to his hometown.

By Monday, it was time to head back to El Paso. I had left a rental car in Presidio, Texas. The plan was for dad to drive me there, and I would then drive to El Paso and fly home. That morning, we visited my uncle before I left. He seemed sadder than usual. My cousin had left to go back to the United States. He would be gone for a while again, and my uncle missed him dearly.

Even as I write this, it is very hard for me to write a detailed account of what happened. Suffice it to say that my uncle attempted suicide that Monday. By Tuesday night, he would be on a ventilator after emergency surgery. I would return to El Paso on Thursday. He would die about a month later. That Monday, dad and I drove the same road on a similarly hot day while chasing the ambulance carrying my uncle.

“If you don’t die a Christian, you won’t get to see him,” she said as my dad looked at the floor and cried.

“I know… I know that,” he replied and cried some more.

The two families that make up my relatives have always been quite religious. The Najeras are Catholic, and devout ones at that. Several of them would take a pilgrimage to Mexico City to visit the basilica there. When Pope John Paul II visited Mexico, it was the highlight of many of their lives. The Padillas are Protestant, belonging to several denominations that span the spectrum of fanaticism. Some are more reasonable than others. Some I like. Others, well…

Protestantism in Chihuahua took time to grow into its own. It had to compete with a very traditional and strong Catholic presence. At first, it attracted the more liberal people who wanted to stray from the strict teachings of the Catholic Church. Later, it began to attract the more conservative folk who thought the Catholic Church was not strong enough to protect certain traditions. This became especially true when Pope Francis took over. He became too liberal for the taste of many, so they flocked to the more conservative Assemblies of God churches which started to pop up.

Andrés’ mother and sisters belong to such church. Apparently, his mother had been pressing my father for years to convert away from Catholicism. She sent preachers to his shop to talk to him, and in his words, “pray away his sins.” This confused dad. He had never been religious, but he thought that being a Catholic — and a good person with good children — was enough. As we sat at the funeral home, Andres’ mother came over and told dad Andrés was in heaven. She then added to my grieving father that he would not see Andrés unless he converted.

There were two religious services for Andrés. The first one was led by a female pastor. She read seemingly at random from the Bible, talking about how Andrés was in heaven… The usual stuff. A male pastor led the second service, and he was the more palatable of the two. He talked about comforting the grieving family, and comforting no matter their beliefs. I thanked him for his message. As a lapsed Christian myself, I needed to hear his words of encouragement and comfort.

I don’t blame Andrés’ mother. She was incredibly angry and sad, heartbroken, you name it… She had lost her oldest boy, a wonderful young man who was good in every way. She was telling my father the best way she knows to see Andrés again. And I don’t blame the religious people for wanting to “save” my father. It’s their whole purpose, to spread what they feel is the best way to live forever. Their timing could have been better, though.

“I’m going to take the long way to El Paso, dad,” I said to him. “I need to clear my mind.”

I’ve always loved the drive from Presidio to El Paso. It’s a hot, dry climate, but the low traffic and pretty vistas help it go by quickly. As I left dad to head back to El Paso one more time — and certainly not the last time — I decided that I was going to mourn Andrés in my own way and drive while thinking things through. I didn’t have my camera with me, so the iPhone 12 camera would have to do.

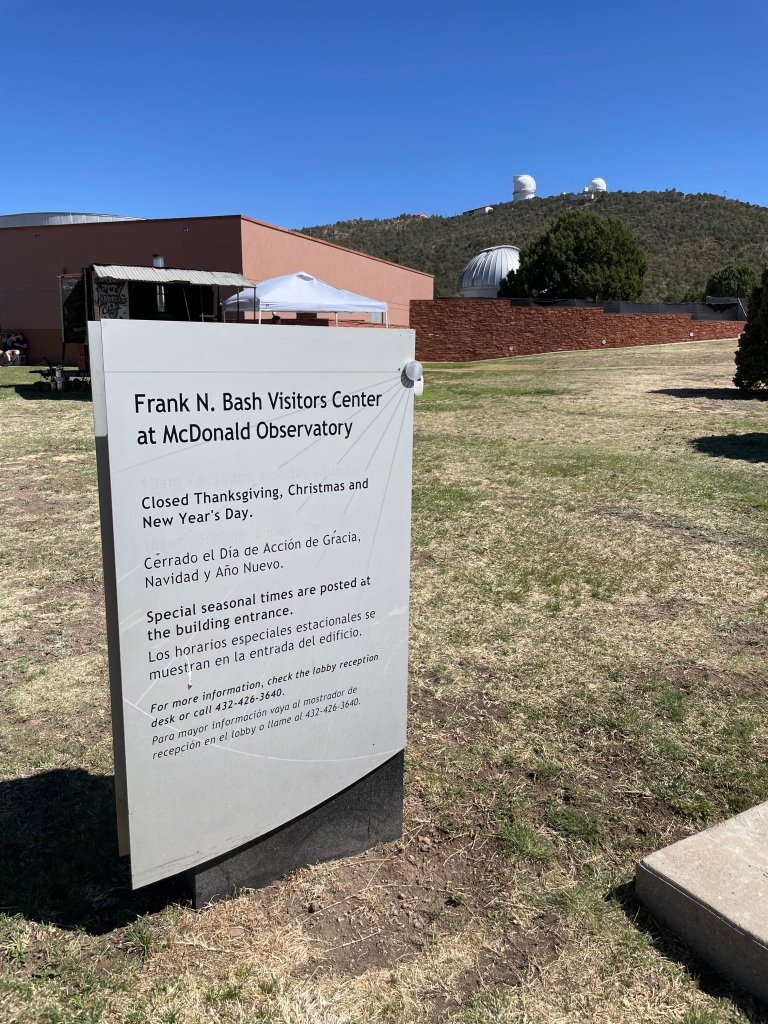

From Presidio, I went north on Highway 67 to Marfa. Along the way, I took pictures of Elephant Rock and the Profile of Lincoln. I then continued on Highway 17 to Fort Davis. I wanted to visit a roadside reptile museum that has many rattlesnakes inside. I hate snakes, but I wanted to just get distracted. It was closed, so I went west on 118 to the McDonald Observatory. There was a festival going on, so I just used the facilities and jumped on the truck on west to Highway 166 south. That was the most beautiful part of the drive. A gorgeous rock formation goes along for the drive for most of the length of the highway until it meets Farm Road 505 toward Valentine, Texas. I then stopped at the Marfa Prada art installation. Then it was time to drive to El Paso and get some sleep before my flight back to Baltimore the next day.

I told dad we would be back as a family (my wife, my daughter, and myself) this summer to pay him a visit. My daughter is five, and he has not met her yet. The distance and the pandemic got in the way, and I’m hoping it doesn’t get in the way again. We probably will fly into Chihuahua City and not El Paso. My wife doesn’t like long drives. Back when we were dating, we drove from San Antonio to Presidio, crossed into Mexico at the Ojinaga border crossing to have lunch with dad, and then drove to El Paso. That was the first time we ever saw the Marfa Prada. She didn’t like the long hours in the car.

I don’t blame her. Texas in general and West Texas in particular are acquired tastes. The dry desert air definitely takes some getting used to after the humid air of the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. But it is all pretty, from a certain point of view.

Andrés and another state police officer died in a vehicle rollover between Ahumada and Juárez, Chihuahua. Two others were transferred to a hospital in Juárez. Andrés was in his third year of service to his city, his state, and his country. He always said he wanted to contribute just “a grain of sand” toward peace in a region torn by wars between drug cartels and decimated by organized crime. And he did.

He did.

Pingback: Let’s Get Caught Up | EpidemioLogical