Your Obsession with Data

Posted on April 2, 2020 2 Comments

As the pandemic continues, one of the questions that I see asked by people all over the country (and the world) is very much, “Where is my data?” For example, in one county in the US, people are clamoring that data be released at the ZIP code level. They want to know where the “hot spots” of COVID-19 are so that they can… Well, they don’t really say what they will do with that information.

The state where this county is located is already under a general quarantine order. People are to stay home unless they are essential personnel in the pandemic response or they perform some sort of essential work function for the public like preparing food, fixing cars or restocking supplies. Everyone else should stay home. So what would change if the average person — who should be home — knows how many cases there are in this or that ZIP code? What changes if they know that they are in or outside of a hot spot?

Some of the same people calling for those data say that they are “high risk” and want to know if it is safe for them in their geographic area. Again, if the order is to stay inside, then what would it change if they were in a hot spot or not? I couldn’t wrap my head around this until someone explained it to me.

Human beings like to think that they have control over stuff. Stuff just happens at random sometimes. Back in October of 2019, an animal was infected with coronavirus. A few of the viruses it was carrying landed on a human being somehow. A few of those had a genetic mutation that allowed them to enter the human cells and replicate. Then thousands of those burst out from this person’s mouth and nose and infected a second person. Two became four. Four became eight… And here we are today.

There is absolutely nothing that any mortal could have done to prevent that genetic accident. Maybe if stronger measures against “wet markets” were in place in China and other parts of the world the “jump” or “spillover” to humans would have been prevented. Maybe. Or maybe if could have been delayed. Maybe.

Now, as was the case with the millions of constitutional scholars that popped up during the impeachment trial, we have millions of epidemiologists who think that they can somehow control their lives and their environment — or glean some insight in to the epidemic — by knowing how many cases there are in a given geographic area. Or they measure their individual risk by looking at who is getting sick and thinking that they are not “those people.” It’s all about control, none of which we really feel like we have if all we do is stay home and play on the internet all day.

So I get it. You want data and you want to analyze it and interpret it your way without really having much training in it because you feel out of control and you want to have some control. Fortunately for us, and unfortunately for you, you’re not getting more than you need to know to be safe. You’re just going to have to come to terms with that and wash your hands and stay home while those of us with years of experience in handling these things do it for you.

That’s how these things work. Your pipe freezes and breaks, so you call the plumber. You don’t stand over the shoulder of the plumber and ask them to give you the data in their heads while they do their work, do you? Do you?

You do? Then we have nothing to talk about.

You don’t? Good. Let the professionals do their work. Have a little faith once in a while.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m heading back once more into the fray.

The White House Knew

Posted on March 21, 2020 1 Comment

Just a quick note about the current pandemic. The White House knew that these things could happen and how bad they could be. Don’t let others tell you otherwise…

From ABC News, 2016:

In the coming days, Trump, along with his top advisers, will begin much more in-depth daily intelligence briefings, along with regular meetings on major diplomatic and international issues. It’s also expected that the White House and Trump’s national security team will conduct a “black swan exercise” in the coming months to simulate what it would be like to manage a major crisis in real time.

https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/donald-trumps-white-house-transition/story?id=43390484

From Foreign Policy Magazine, 2018:

In January 2017, while one of us was serving as a homeland security advisor to outgoing President Barack Obama, a deadly pandemic was among the scenarios that the outgoing and incoming U.S. Cabinet officials discussed in a daylong exercise that focused on honing interagency coordination and rapid federal response to potential crises. The exercise is an important element of the preparations during transitions between administrations, and it seemed things were off to a good start with a commitment to continuity and a focus on biodefense, preparedness, and the Global Health Security Agenda—an initiative begun by the Obama administration to help build health security capacity in the most critically at-risk countries around the world and to prevent the spread of infectious disease. But that commitment was short-lived.

https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/09/28/the-next-pandemic-will-be-arriving-shortly-global-health-infectious-avian-flu-ebola-zoonotic-diseases-trump/

…

The prevailing laissez-faire attitude toward funding pandemic preparedness within President Donald Trump’s White House is creating new vulnerabilities in the health infrastructure of the United States and leaving the world with critical gaps to contend with when the next global outbreak of infectious disease hits.

The investments made after the 2014 Ebola crisis have been slashed in recent proposed federal budgets from the Centers for Disease Control, the agency that works to stop deadly diseases in their tracks, and the U.S. Agency for International Development, which responds to international disasters, including the Ebola outbreak. Moreover, Timothy Ziemer, the top White House official in charge of pandemic preparedness, has left his job, and the biosecurity office he ran was summarily disbanded.

From Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security, 2017:

To serve as baseline information for the incoming new Administration and Congress, the scholars at the Center for Health Security wrote a series of commentaries providing facts and assessments of what has been accomplished in key areas of health security and what needs to be done now. They highlighted some ambitious goals that could, if embraced by the new Administration, significantly advance our national ability to save lives, economies, and societies when faced with serious health security threats. Some of these goals have been aspired to for a long time, but there has not been the kind of national commitment to fully achieve them.

http://www.centerforhealthsecurity.org/who-we-are/annual_report/pdfs/2017-CHS-annual-report.pdf

Those are all articles written before 2019. I wanted to find articles from then that should have warned us about today. And here we are. Stay safe.

The Pandemics You Can Try to Stop

Posted on March 18, 2020

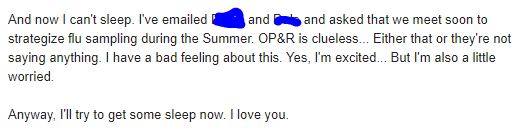

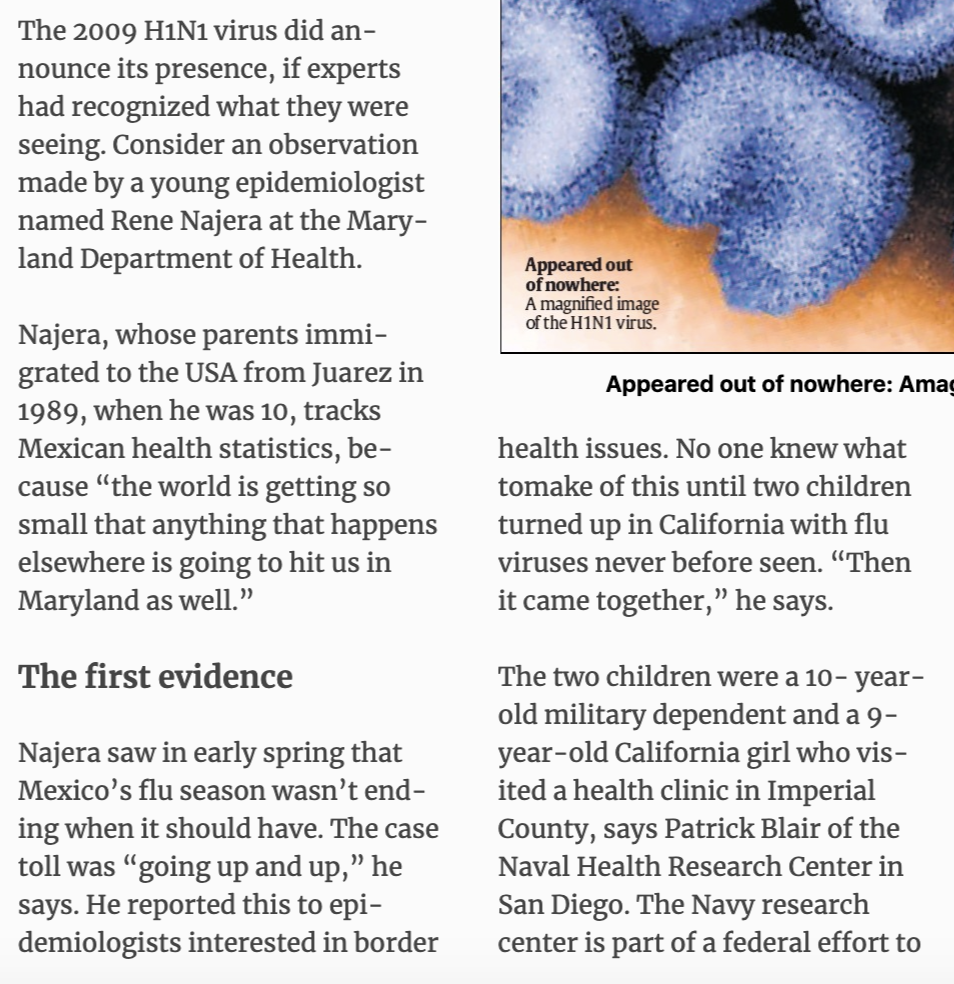

In mid-April 2009, I noticed that the influenza season in Mexico had not ended the way it should. I contacted friends and acquaintances in Mexico City and other parts of the country to ask them what they were seeing. Epidemiologist colleagues told me that they had noticed the same thing. A season that should have been trending down was not doing so, and local hospitals and clinics were being overrun by people with respiratory symptoms.

That night, I emailed my fiancee (now my wife) and told her that I had a bad feeling about what was going on. I told her that it made no sense for Mexico to still be seeing their season being so prolonged. The US season was winding down, though. I remember writing to her that I hoped I was wrong.

After that whole thing was done and over with in 2010 (because it swung around and hit us twice in 2009), I wondered if there was something that we could have done to stop it. By “we,” I mean us in public health. At the time, I was just a freshman epidemiologist with a couple of years of experience. In ten years time, I would be a doctor of public health, and we would be facing another pandemic… The next pandemic.

Can pandemics be stopped? In one word: Yes. But it is very complicated. For example, the HIV/AIDS pandemic could have been stopped if enough resources had been put into place the minute it was identified as a sexually-transmitted infection. HIV was infecting the “undesirables,” though, and enough leaders (religious and political) were calling it a godsend to get rid of said undesirables. It was a punishment from above, not the continuation of a zoonosis that had started decades earlier.

Respiratory infections are a whole other animal, though, especially the ones with relatively (RELATIVELY) low fatality rates. Those with higher rates, like Ebola, kill the hosts before the infection is spread too widely. (Global travel is challenging that, however.) Those that infect you, incubate, and then attack but leave you well enough to have you go to school or work have the ability to really cause disruptions.

I mean, look out the window right now if you’re March 2020.

Bacterial pandemics, like the ones that cholera has caused, are mostly under control by our ability to deploy control measures (clean water and vaccines) and antibiotics. But we’re also entering a sort of “post-antibiotic” era where bacteria are evolving faster than we can make antibiotics against them. So future bacterial pandemics will also require control measures that are not pharmaceutical in nature.

What we can do — and we should do at the end of this pandemic — is have a foolproof, well-researched, practiced yearly, top-of-the-line pandemic preparedness plan that spans the entire spectrum of everything we know has happened and could happen. From what a person will do in their everyday life to what small businesses will do when left with no workers and no employees, to what big groups and organizations will do to keep the disease from spreading. We can’t go blind into the next one — like we did into this one — because the next one could be the big one.

Then there are the epidemics and pandemics of non-communicable diseases, like obesity, diabetes and opioid use/abuse. Those are going to be super-difficult to figure out, perhaps more difficult than infectious disease. This is because we are social animals who’ve managed to separate into tribes and social strata. If something is happening to “them” and not “us,” and it will stay “over there” and not come “here,” we kind of look the other way.

Here’s an example… In Philadelphia, like in other cities in the United States, there is an epidemic of opioid use and opioid overdoses going on. Many of the people using and abusing opioids are using heroin, an injected opioid. (You can also smoke it, by the way.) When people inject heroin and other drugs, their risk for blood borne infections skyrockets. They share needles or trade drugs for sex (that is performed unsafely), and they get infections with Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C and HIV.

Look at what is happening in Minnesota.

Look at what happened in Indiana, that bastion of public health.

No doubt, Philadelphia is lining up to be the next epicenter of both overdose and blood born infections… If it isn’t already. To counter this, city health officials and health leaders have proposed a safe injection site. In a safe injection site, the user goes in, gets a clean needle and a place to rest. They get medical supervision while they use their drug of choice. Should something go sideways, they get immediate medical attention.

But drug addiction — against all evidence — is thought by many to be something that happens to “them,” the “others,” the undesirables. It doesn’t happen to “us,” the clean people, the God-fearing people. And if something is to be done for “those poor people,” it better not be done in our back yard, or my neighborhood, or anywhere that could possibly make me think that help is happening at all.

On Monday, March 16, 2020, supporters and detractors of a safe injection site in Philadelphia came together to give their opinion on a bill that would ban such help for “those people.” As you can imagine, the discussion was lively, including some gems like:

“Why would we want to be the first to experiment on this?… “It makes no sense whatsoever. I’m full of compassion for [people suffering from drug addiction], but I’m more full of compassion for my residents and all the residents symbolized by these civic associations.”

There are no safe injection sites in the United States, but there are plenty in other parts of the world. Those other sites have shown success in reducing overdoses and in guiding users into recovery programs. On top of receiving clean needles and medical supervision, they also are referred to care, and many of them take it. Some place in the United States, a place where these programs are needed, is going to be the first place, the “experiment.”

But the comments did not stop there.

Capozzi’s sentiment was echoed in the testimony of South Philly resident Anthony Giordano, who represented a community group called Stand Up South Philly and Take Our Streets Back.

“Safe injection sites are not safe,” he said. “Allowing people to consume illegal drugs of unknown composition in a so-called medical facility is beyond my comprehension. How is this safe? Helping people further harm themselves under the guise of a legitimate medical intervention just doesn’t make any sense.”

Some people tried to use science and reason:

“It amazes me that we’re sitting here talking about making a medical decision and we’re listening to public opinion,” she said. “We need to make this based on information like Dr. Farley suggested: medical consensus, meta-analyses and a medical opinion.”

Milas was unique among the four medical professionals because the opioid crisis had affected her a bit more personally. She had two sons die of opioid overdoses – one was 27 and other 31, she said.

“At the 100 legal supervised injection sites worldwide, there are no recorded deaths,” she testified. “Had my sons overdosed at a Safehouse-type facility, they would have had a 100 percent chance of survival.”

Roth piled on.

“The scientific evidence from peer-reviewed journals on these sites is clear,” she testified. “They reduce overdose mortality rates, HIV, environmental hepatitis risk, they improve access to health and social services, they help reduce substance use and help people enroll in treatment. Furthermore, they’ve helped improve community health and safety. In neighborhoods where a [safe injection site] exists, there are actually reductions in public injection and improperly discarded syringes, reductions in drug-related crime, and the demand for ambulance services for opioid-related overdoses goes down.”

You can read the rest of the South Philly Review article to see how one of the legislators used a very flawed non-scientific “study” to support his claims that safe injection sites are absolute evil. That’s where scientific discourse in public policy has gone… To unsubstantiated and flawed opinion surveys.

As I’ve stated before, several times, public health in the United States and in much of the world is all about politics. You better pray that the right political party is in power, or the right people are in power, so that the decisions that need to be made are informed by evidence and science more than the “what ifs” of public opinion. This is Democracy getting in the way of things, unfortunately.

As we saw in Wuhan, China, when authorities there felt the need to shut down cities, they did so without any apparent issues. (There might have been issues, but we’ll be darned if we ever find out.) That’s an authoritarian government for you in a very collectivist society. Can you imagine trying to shut down even a small town here in the United States? With people with guns? And SUVs?

Good luck.

So, yeah, we might not be able to stop this pandemic, or the next one. After all this, I’m going to focus on having what I call “premier” surveillance systems and response plans. We’re going to learn a lot from this pandemic, and I plan to make it my life’s work (on top of all of my other work) to make sure we don’t forget about this time, next time.

Until next time… Thanks for your time.

The Panic People Will Have

Posted on March 9, 2020 3 Comments

There are some words that really get people all riled up. “Pandemic” is one of them. While the technical definition of pandemic is a worldwide epidemic, regardless of severity, a lot of people associate the word with some sort of unmitigated disaster.

I don’t blame people for thinking that way. After all, most of us are told the story of the 1918 Spanish Influenza pandemic that killed millions around the world. We also hear of other pandemics that have done a number on the human populations, like the Black Death (Yersinia pestis) and the still ongoing pandemic of HIV/AIDS.

There was even some doctor teaching out in California who once got all snippy with me because he said that we (epidemiologists) should not be using the term “pandemic” when not a lot of people die. (And then said that I was salty for not being a doctor — in 2009 — and not having any kind of authority to correct him.) He wanted some other term to be used, but he fell short of actually suggesting something that mean “a worldwide epidemic.”

This latest pandemic of coronavirus is different from the last one (2009 H1N1 influenza) because social media has become such an enormous source of information — and misinformation — for so many people. Too many people are getting their news from other people who have zero knowledge of journalism, let alone science. So you end up with people doing some very “interesting” things.

First, they came for the water. I went to the store a couple of weeks ago, and they were already out of bottled water. One of the employees said that a lot of people had shown up early to buy up every case and container of drinking water they could find. Interestingly, and perhaps showing people’s lack of science knowledge, they left the distilled water behind. Distilled water is purified water and perfectly safe to drink. For some reason, according to the employee, people were not buying it because they thought they could not drink it.

Weird, right?

Then they came for the toilet paper. I keep seeing news articles and videos of people fighting each other to buy up extra toilet paper. This one really puzzles me. I mean, it’s a joke that people will buy bread, milk and toilet paper before a big snowstorm, but they are doing this at this time because… Because they’re going to be pooping a lot at home if they have to stay home for a couple of weeks?

People are at such a panic that the stock market is taking a hit. Because so many coronavirus cases have been on cruise ships and in people traveling abroad, the touring industry is taking a hit. Because all those ships and all those planes are not using as much fuel, the oil industry is taking a hit. And because people won’t gather at large events, the sports and entertainment industries are taking a hit.

All of this almost makes me want to take a hit.

Humans are animals. Not only that, they’re also animals who run in packs. If one starts running in one direction, the chances are that others will start going in the same direction. Before you know it, you’re facing a stampede. Only a few will stand aside and watch the show, sometimes to their own detriment. And even fewer will run in the other direction — towards danger — to see if there is something they can do to help stop what is making people afraid.

As people are running to buy toilet paper and hand sanitizer, others are running with them. As they run away from ships and planes where the disease is being spread, others are running with them. And as they run to the warm embrace of social media, others are running with them.

Me? I’m running in the other direction. Not only is it something I’ve always seem to do, it is also my job.

You can thank my mom for that.

Local Indicators of Spatial Association in Homicides in Baltimore, 2019

Posted on March 3, 2020 2 Comments

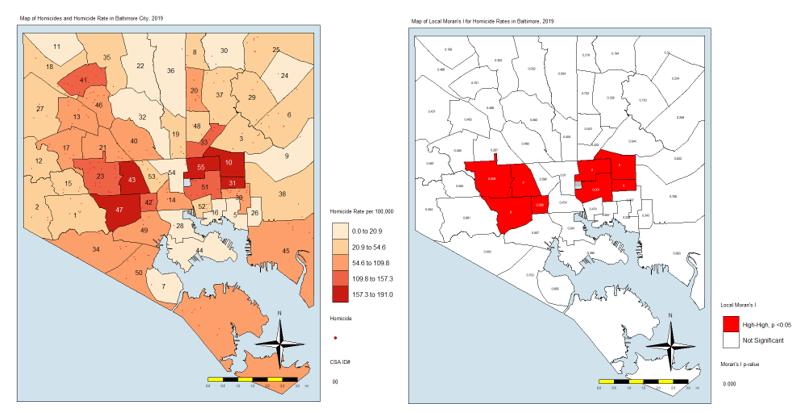

Last year was yet another record year for homicides in Baltimore with 348 reported homicides for the year. While this number was the second-highest in terms of total homicides, it was probably the highest in terms of rate per 100,000 residents since Baltimore has been seeing a decrease in population. (The previous record was in 2015 and 2017.) The epidemic of violence and homicides that began in 2015 continues today.

When we epidemiologists analyze data, we need to be mindful of the spatial associations we see. The first law of geography states that “everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things.” As a result, clusters of cases of a disease or condition — or an outcome such as homicides — may be more a factor of similar things happening in close proximity to each other than an actual cluster.

To study this phenomenon and account for it in our analyses, we use different techniques to assess spatial autocorrelation and spatial dependence. In this blog post, I will guide you through doing a LISA (Local Indicators of Spatial Association) analysis of homicides in Baltimore City in 2019 using R programming.

First, The Data

Data on homicides was extracted from the Baltimore City Open Data portal. Under the “Public Safety” category, we find a data set titled “BPD Part 1 Victim Based Crime Data.” In those data, I filtered the observations to be only homicides and only those occurring/reported in 2019. This yielded 348 records, corresponding to the number reported for the year.

Data on Community Statistical Areas (agglomerations of neighborhoods based on similar neighborhood characteristics came from the Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance (BNIA). They are a very good source of data on Baltimore with regards to social and demographic indicators. From their open data portal, I extracted the shapefile of CSAs in the city.

Next, The R Code

First, I load the libraries that I’m going to use for this project. (I’ve tried to annotate the code as much as possible.)

library(tidyverse)

library(rgdal)

library(ggmap)

library(spatialEco)

library(tmap)

library(tigris)

library(spdep)

library(classInt)

library(gstat)

library(maptools)Next, I load the data.

csas <-

readOGR("2017_csas",

"Vital_Signs_17_Census_Demographics") # Baltimore Community Statistical Areas

jail <-

readOGR("Community_Statistical_Area",

"community_statistical_area") # For the central jail

pro <-

sp::CRS("+proj=longlat +datum=WGS84 +unit=us-ft") # Projection

csas <-

sp::spTransform(csas,

pro) # Setting the projection for the CSAs shapefile

homicides <- read.csv("baltimore_homicides.csv",

stringsAsFactors = F) # Homicides in Baltimore

homicides <-

as.data.frame(lapply(homicides, function(x)

x[!is.na(homicides$Latitude)])) # Remove crimes without spatial data (i.e. addresses)Note that I had to do some wrangling here. First, there is an area on the Baltimore Map that corresponds to a large jail complex in the center of the city. So I added a second map layer called jail to the data. I also corrected the projection on the layers. (This helps make sure that the points and polygons line up correctly since you’re overlaying a flat piece of data on a spherical part of the planet.) Finally, I took out homicides for which there was no spatial data. This sometimes happens when the true location of a homicide cannot be determined… Or when there is a lag/gap in data entry.

Next, I’m going to convert the homicides data frame into a spatial points file.

coordinates(homicides) <-

~ Longitude + Latitude # Makes the homicides CSV file into a spatial points file

proj4string(homicides) <-

CRS("+proj=longlat +datum=WGS84 +unit=us-ft") # Give the right projection to the homicides spatial pointsNote that I am telling R which variables in homicides corresponds to the longitude and latitude variables. Next, as I did before, I corrected the projection to match that of the CSAs layer.

Now, let’s join the points (homicides) to the polygons (csas).

homicides_csas <- point.in.poly(homicides,

csas) # Gives each homicide the attributes of the CSA it happened in

homicide.counts <-

as.data.frame(homicides_csas) # Creates the table to see how many homicides in each CSA

counts <-

homicide.counts %>%

group_by(CSA2010, tpop10) %>%

summarise(homicides = n()) # Determines the number of homicides in each CSA.

counts$tpop10 <-

as.numeric(levels(counts$tpop10))[counts$tpop10] # Fixes tpop10 not being numeric

counts$rate <-

(counts$homicides / counts$tpop10) * 100000 # Calculates the homicide rate per 100,000

map.counts <- geo_join(csas,

counts,

"CSA2010",

"CSA2010",

how = "left") # Joins the counts to the CSA shapefile

map.counts$homicides[is.na(map.counts$homicides)] <-

0 # Turns all the NA's homicides into zeroes

map.counts$rate[is.na(map.counts$rate)] <-

0 # Turns all the NA's rates into zeroes

jail <-

jail[jail$NEIG55ID == 93, ] # Subsets only the jail from the CSA shapefileHere, I also created a table to see how many points fell inside the polygons. I allowed me to look at how many homicides were in each of the CSAs. Here are the top five:

| Community Statistical Area | Homicide Count |

| Southwest Baltimore | 29 |

| Sandtown-Winchester/Harlem Park | 25 |

| Greater Rosemont | 21 |

| Clifton-Berea | 16 |

| Greenmount East | 15 |

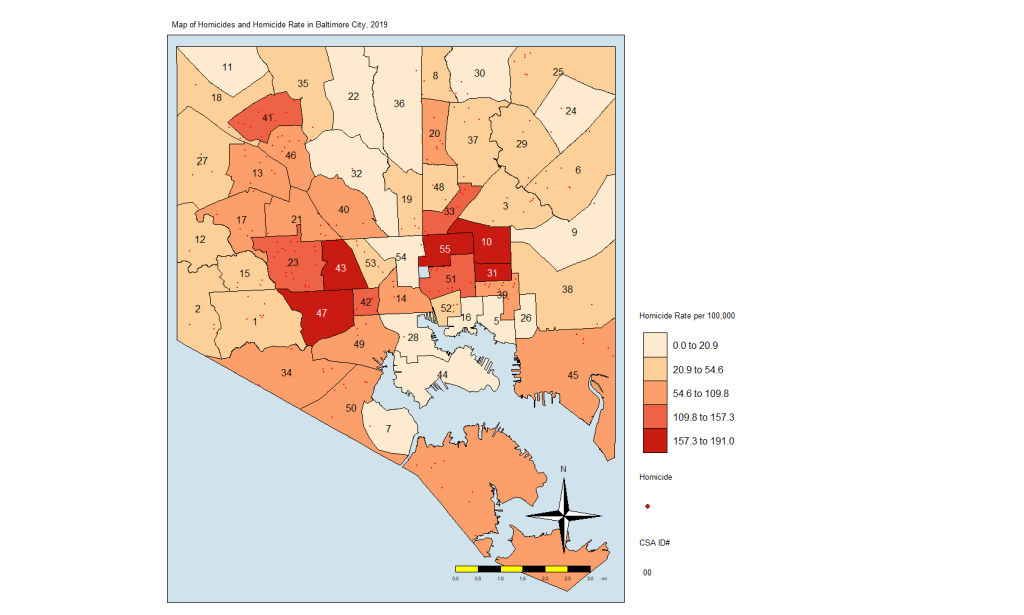

Of course, case counts alone are not giving us the whole information. We need to account for the differences in population numbers. For that, you’ll see that I created a rate variable. Here are the top five CSAs by homicide rate per 100,000 residents:

| Community Statistical Area | Homicide Rate per 100,000 Residents |

| Greenmount East | 191 |

| Sandtown-Winchester/Harlem Park | 189 |

| Clifton-Berea | 176 |

| Southwest Baltimore | 172 |

| Madison/East End | 167 |

As you can see, the ranking based on homicide rates is different, but it is more informative. It accounts for the fact that you may see more homicides in a CSA simply because that CSA has more people in it. Now we have the rates. I then joined the counts and rates to the csas shapefile. This is what we’ll use to map. I also made sure that all the NA’s in the rates and counts are zeroes. Finally, I used only the CSA labeled “93” for the jail. This, again, is to make sure that the map represents that area and we know that it is not a place where people live.

The Maps

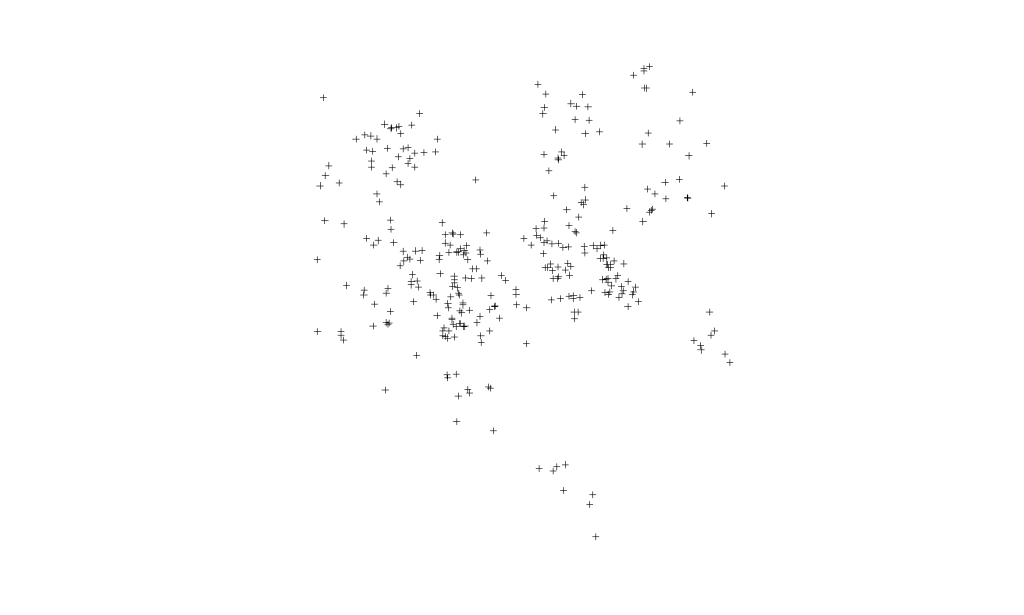

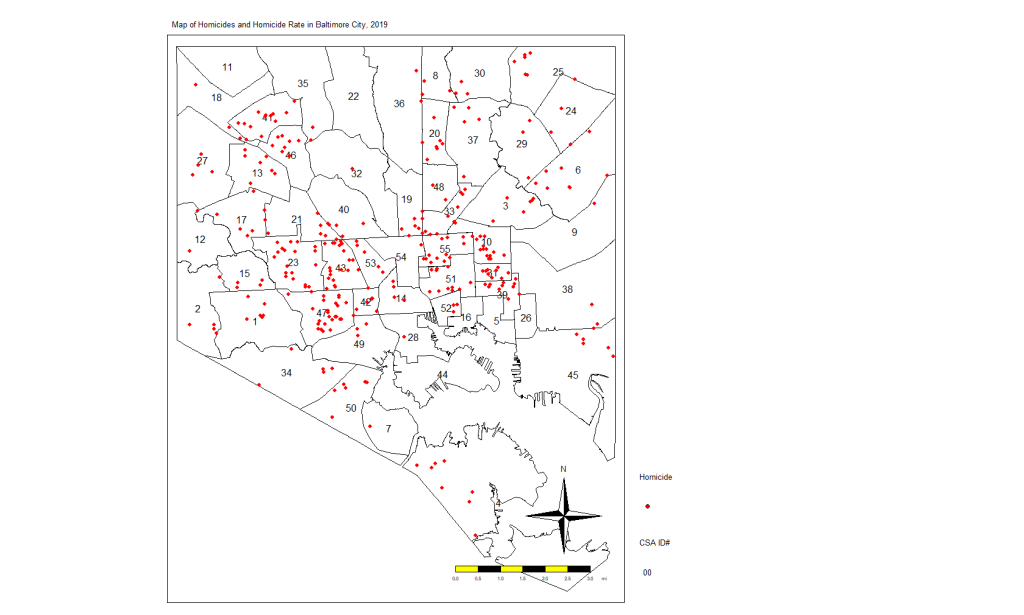

Look at the following simple plot of homicide locations in Baltimore:

This is not a map. This is just a plot of the homicide locations. The latitude is on the Y axis and the longitude on the X axis. If you notice that there is some clustering of cases, you would be correct. Point-based cluster analysis can also be done on these data alone, but that is for a different blog post at a later time. (And you have to take other things into consideration.)

Next, I’m going to create a map of the points above (using the tmap package) but also show the boundaries of the CSAs. This will look more like a map and show you the spatial distribution of the homicide cases in context. You’ll see why there are blank spaces in some parts.

Here is the code:

tmap_mode("plot") # Set tmap to plot. To make interactive, use "view"

homicide.dots.map <-

tm_shape(map.counts) +

tm_borders(col = "black",

lwd = 0.5) +

tm_text("OBJECTID",

size = 1) +

tm_shape(homicides) +

tm_dots(col = "red",

title = "2019 Homicides",

size = 0.2, ) +

tm_compass() +

tm_layout(

main.title = "Map of Homicides and Homicide Rate in Baltimore City, 2019",

main.title.size = 0.8,

legend.position = c("left", "bottom"),

compass.type = "4star",

legend.text.size = 1,

legend.title.size = 1,

legend.outside = T

) +

tm_scale_bar(

text.size = 0.5,

color.dark = "black",

color.light = "yellow",

lwd = 1

) +

tm_add_legend(

type = "symbol",

col = "red",

shape = 21,

title = "Homicide",

size = 0.5

) +

tmap_options(unit = "mi") +

tm_add_legend(

type = "text",

col = "black",

title = "CSA ID#",

text = "00"

)

homicide.dots.map

And here is the map:

Again, we see the clustering of homicides in some areas. Let’s look at homicide rates. First, the code:

homicide.rate.map <-

tm_shape(map.counts) +

tm_fill(

"rate",

title = "Homicide Rate per 100,000",

style = "fisher",

palette = "OrRd",

colorNA = "white",

textNA = "No Homicides"

) +

tm_borders(col = "black",

lwd = 0.5) +

tm_text("OBJECTID",

size = 1) +

tm_shape(homicides) +

tm_dots(col = "red",

title = "2019 Homicides") +

tm_shape(jail) +

tm_fill(col = "#d0e2ec",

title = "Jail") +

tm_compass() +

tm_layout(

main.title = "Map of Homicides and Homicide Rate in Baltimore City, 2019",

main.title.size = 0.8,

legend.position = c("left", "bottom"),

compass.type = "4star",

legend.text.size = 1,

legend.title.size = 1,

bg.color = "#d0e2ec",

legend.outside = T

) +

tm_scale_bar(

text.size = 0.5,

color.dark = "black",

color.light = "yellow",

lwd = 1

) +

tm_add_legend(

type = "symbol",

col = "red",

shape = 21,

title = "Homicide",

size = 0.5

) +

tm_add_legend(

type = "text",

col = "black",

title = "CSA ID#",

text = "00"

) +

tmap_options(unit = "mi")

homicide.rate.mapIt stands to reason that the CSAs with the most points would also have the highest rates, so here is the map:

From here, we see that the CSAs with the highest rates are close together. We also see that those with the lowest rates are close together. And others are somewhere in between. If there was no spatial autocorrelation, we would expect these CSAs with high or low rates to be equally distributed all over the map. If there was perfect autocorrelations, all highs would be on one side and all lows would be on the other. What we have here is something in the middle, as is the case in most real-life examples.

LISA Analysis

In the next few lines of code, I’m going to do several things. First, I’m going to create a list of the neighbors to each CSA. One CSA, #4 at the far southern tip of the city, does not touch other CSAs. It looks like an island. So I’m going to manually add its neighbors to the list.

Next, I’m going to create a list of neighbors and weights. By weights, I mean that each neighbor will “weigh” the same. If a CSA has one neighbor, then the weight of that neighbor is 1. If they have four, each neighbor — to that CSA — weighs 0.25.

Next, I’m going to calculate the Local Moran’s I value. For a full discussion of Moran’s I, I recommend you visit this page: http://ceadserv1.nku.edu/longa//geomed/ppa/doc/LocalI/LocalI.htm

There are a lot of nuances to that value. But, basically, that value tells us how different from no spatial autocorrelation each CSAs is. Once you see it on the map, you’ll understand better.

Here’s the code:

map_nbq <-

poly2nb(map.counts) # Creates list of neighbors to each CSA

added <-

as.integer(c(7, 50)) # Adds neighbors 7 and 50 to CSA 4 (it looks like an island)

map_nbq[[4]] <- added # Fixes the region (4) without neighbors

View(map_nbq) # View to make sure CSA 4 has neighbors 7 and 50.

map_nbq_w <-

nb2listw(map_nbq) # Creates list of neighbors and weights. Weight = 1/number of neighbors.

View(map_nbq_w) # View the list

local.moran <-

localmoran(map.counts$rate, # Which variable you'll use for the autocorrelation

map_nbq_w, # The list of weighted neighbors

zero.policy = T) # Calculate local Moran's I

local.moran <- as.data.frame(local.moran)

summary(local.moran) # Look at the summary of Moran's I

map.counts$srate <-

scale(map.counts$rate) # save to a new column the standardized rate

map.counts$lag_srate <- lag.listw(map_nbq_w,

map.counts$srate) # Spatially lagged standardized rate in new column

summary(map.counts$srate) # Summary of the srate variable

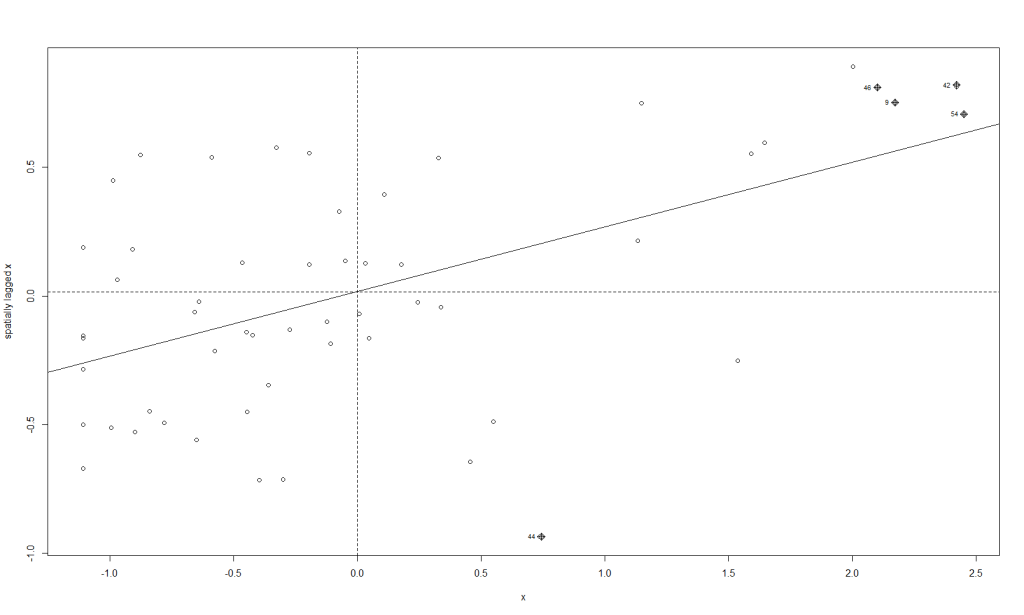

summary(map.counts$lag_srate) # Summary of the lag_srate variableNow, we’ll take a look at the Moran’s I plot created with this code:

x <- map.counts$srate %>% as.vector()

y <- map.counts$lag_srate %>% as.vector()

xx <- data.frame(x, y) # Matrix of the variables we just created

moran.plot(x, map_nbq_w) # One way to make a Moran PlotAnd here is the plot:

This plot tells us which CSAs are in the High-High (right upper quadrant), High-Low (right lower quadrant), Low-Low (left lower quadrant) and Low-High (left upper quadrant) designations for Moran’s I values. The High-High CSAs mean that their value was high and the values of the CSAs (their neighbors) were high also. That is expected since everything is like everything else close to it, right?

The Low-Low CSAs are the same. The ones that are outlier in this regard are the High-Low and Low-High, because these are CSAs that are high values (by values, we are looking at a calculation derived from standardized homicide rates) in a sea of low values, or low values in a sea of high values. The plot above has highlighted the ones that are not spatial outliers and have a significant p-value. (More on the p-value later.)

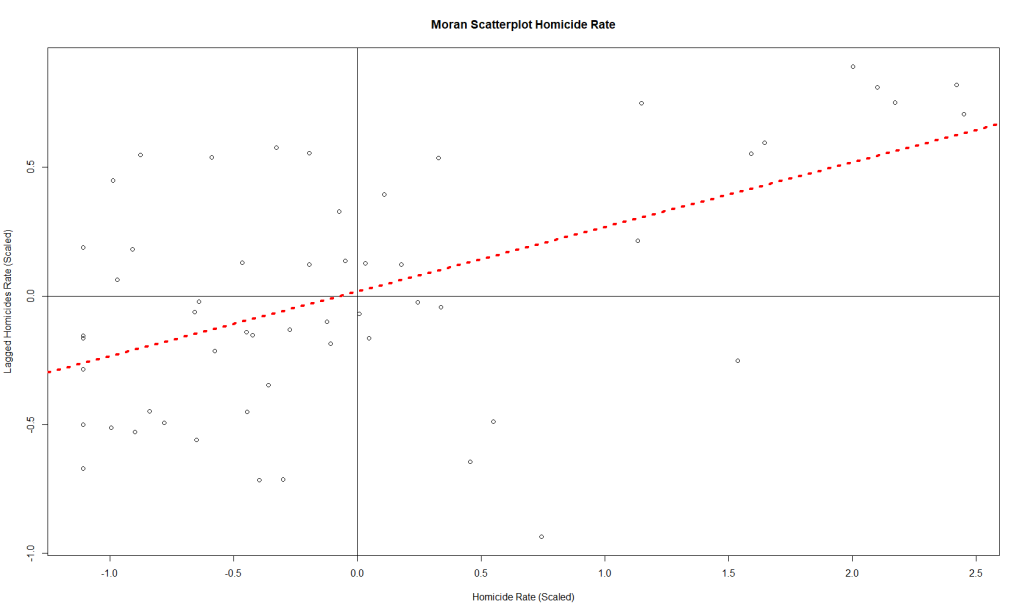

There is another way to make the same plot, if you’re so inclined:

plot(

x = map.counts$srate,

y = map.counts$lag_srate,

main = "Moran Scatterplot Homicide Rate",

xlab = "Homicide Rate (Scaled)",

ylab = "Lagged Homicides Rate (Scaled)"

) # Another way to make a Moran Plot

abline(h = 0,

v = 0) # Adds the crosshairs at (0,0)

abline(

lm(map.counts$lag_srate ~ map.counts$srate),

lty = 3,

lwd = 4,

col = "red"

) # Adds a red dotted line to show the line of best fitAnd this is the resulting plot from that:

So those are the plots of the Moran’s I value. What about a map of these values? For that, we need to prepare our CSAs with the appropriate quadrant designations.

map.counts$quad <-

NA # Create variable for where the pair falls on the quadrants of the Moran plot

map.counts@data[(map.counts$srate >= 0 &

map.counts$lag_srate >= 0), "quad"] <-

"High-High" # High-High

map.counts@data[(map.counts$srate <= 0 &

map.counts$lag_srate <= 0), "quad"] <-

"Low-Low" # Low-Low

map.counts@data[(map.counts$srate >= 0 &

map.counts$lag_srate <= 0), "quad"] <-

"High-Low" # High-Low

map.counts@data[(map.counts$srate <= 0 &

map.counts$lag_srate >= 0), "quad"] <-

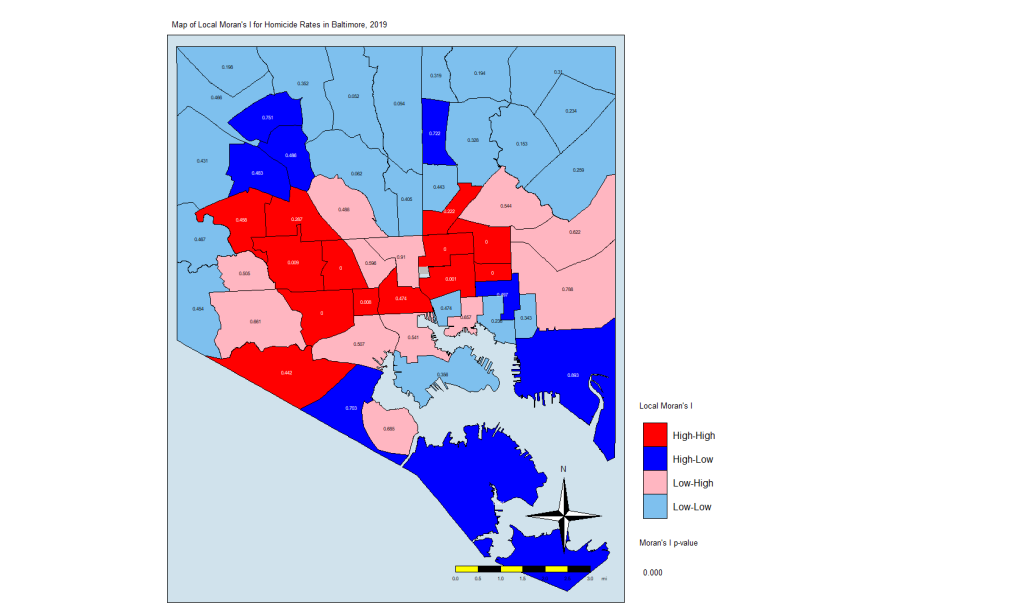

"Low-High" # Low-HighThis gives us this map:

Here is the code for that map:

local.moran$OBJECTID <- 0 # Creating a new variable

local.moran$OBJECTID <- 1:nrow(local.moran) # Adding an object ID

local.moran$pvalue <-

round(local.moran$`Pr(z > 0)`, 3) # Rounding the p value to three decimal places

map.counts <- geo_join(map.counts,

local.moran,

"OBJECTID",

"OBJECTID")

colors <-

c("red", "blue", "lightpink", "skyblue2", "white") # Color Palette

local.moran.map <-

tm_shape(map.counts) +

tm_fill("quad",

title = "Local Moran's I",

palette = colors,

colorNA = "white") +

tm_borders(col = "black",

lwd = 0.5) +

tm_text("pvalue",

size = 0.5) +

tm_shape(jail) +

tm_fill(col = "gray",

title = "Jail") +

tm_compass() +

tm_layout(

main.title = "Map of Local Moran's I for Homicide Rates in Baltimore, 2019",

main.title.size = 0.8,

legend.position = c("left", "bottom"),

compass.type = "4star",

legend.text.size = 1,

legend.title.size = 1,

legend.outside = T,

bg.color = "#d0e2ec"

) +

tm_scale_bar(

text.size = 0.5,

color.dark = "black",

color.light = "yellow",

lwd = 1

) +

tm_add_legend(

type = "text",

col = "black",

title = "Moran's I p-value",

text = "0.000"

) +

tmap_options(unit = "mi")

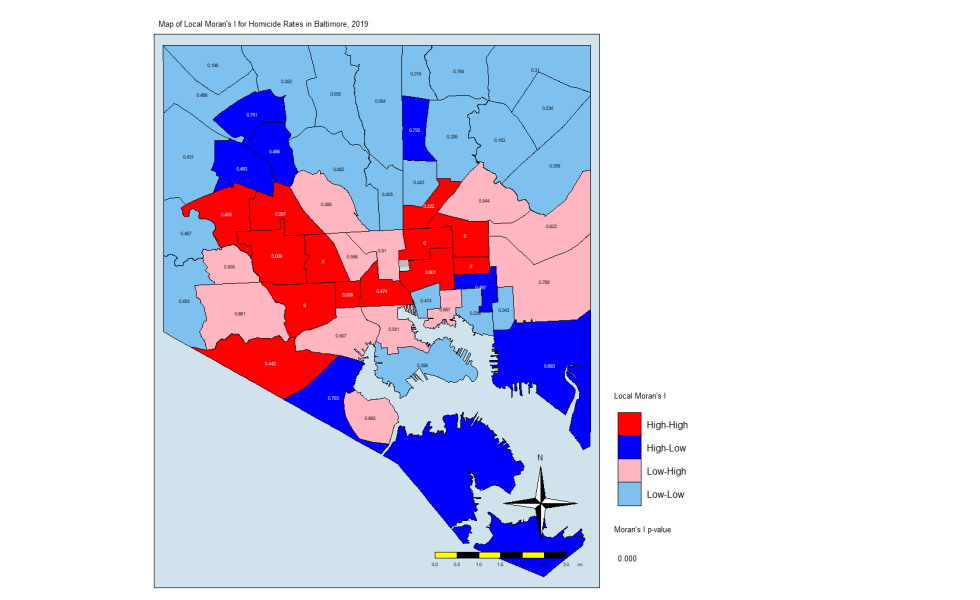

local.moran.mapThe CSAs in red are those that have high Moran’s I values and are surrounded by other CSAs with high values. The light blues are where there are low values and are are surrounded by lows. The dark blue are CSAs with high values but with low neighbors, and the light pink are CSAs with low values but high neighbors. The numbers inside each CSA is the p-value.

The Thing About Significance

If you’ve done your coursework on biostatistics, you’ll see that there is a lot of attention paid to p-values that are less than 0.05. In this case, only a few CSAs have such low p-values. But that may not be enough. In this explainer on spatial association, the author states the following:

An important methodological issue associated with the local spatial autocorrelation statistics is the selection of the p-value cut-off to properly reflect the desired Type I error. Not only are the pseudo p-values not analytical, since they are the result of a computational permutation process, but they also suffer from the problem of multiple comparisons (for a detailed discussion, see de Castro and Singer 2006). The bottom line is that a traditional choice of 0.05 is likely to lead to many false positives, i.e., rejections of the null when in fact it holds.

Source: https://geodacenter.github.io/workbook/6a_local_auto/lab6a.html

For this exercise, we are going to keep the p-value significance at 0.05 and create a map that uses the resulting CSAs. The code:

map.counts$quad_sig <-

NA # Creates a variable for where the significant pairs fall on the Moran plot

map.counts@data[(map.counts$srate >= 0 &

map.counts$lag_srate >= 0) &

(local.moran[, 5] <= 0.05), "quad_sig"] <-

"High-High, p <0.05" # High-High

map.counts@data[(map.counts$srate <= 0 &

map.counts$lag_srate <= 0) &

(local.moran[, 5] <= 0.05), "quad_sig"] <-

"Low-Low, p <0.05" # Low-Low

map.counts@data[(map.counts$srate >= 0 &

map.counts$lag_srate <= 0) &

(local.moran[, 5] <= 0.05), "quad_sig"] <-

"High-Low, p <0.05" # High-Low

map.counts@data[(map.counts$srate <= 0 &

map.counts$lag_srate >= 0) &

(local.moran[, 5] <= 0.05), "quad_sig"] <-

"Low-High, p <0.05" # Low-High

map.counts@data[(map.counts$srate <= 0 &

map.counts$lag_srate >= 0) &

(local.moran[, 5] <= 0.05), "quad_sig"] <-

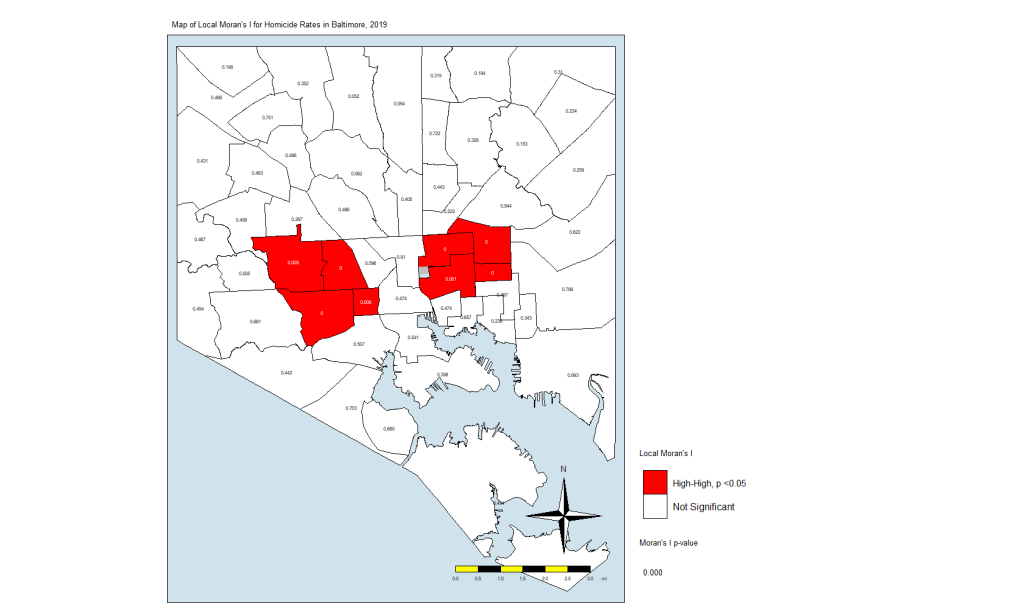

"Not Significant. p>0.05" # Non-significantNote that I am using the p-value in the local.moran calculation (position #5) in addition to where on the moran plot the CSAs fall. This really eliminates the non-significant (at p = 0.05) CSAs and leaves us with only eight CSAs. Here is the code for the map:

local.moran.map.sig <-

tm_shape(map.counts) +

tm_fill(

"quad_sig",

title = "Local Moran's I",

palette = colors,

colorNA = "white",

textNA = "Not Significant"

) +

tm_borders(col = "black",

lwd = 0.5) +

tm_text("pvalue",

size = 0.5) +

tm_shape(jail) +

tm_fill(col = "gray",

title = "Jail") +

tm_compass() +

tm_layout(

main.title = "Map of Local Moran's I for Homicide Rates in Baltimore, 2019",

main.title.size = 0.8,

legend.position = c("left", "bottom"),

compass.type = "4star",

legend.text.size = 1,

legend.title.size = 1,

legend.outside = T,

bg.color = "#d0e2ec"

) +

tm_scale_bar(

text.size = 0.5,

color.dark = "black",

color.light = "yellow",

lwd = 1

) +

tm_add_legend(

type = "text",

col = "black",

title = "Moran's I p-value",

text = "0.000"

) +

tmap_options(unit = "mi")

local.moran.map.sigAnd here is the map itself:

What this is telling us is that only those eight CSAs had a statistically significant Moran’s I value, and they were all in the “High-High” classification. This means that they have high standardized values (which are themselves derived from homicide rates) and are surrounded by CSAs with high values. There were no significant CSAs from the other quadrants on the Moran plot. (Remember that significance here comes with a big caveat.)

In Closing

What does this all mean? It means that the “butterfly pattern” seen in so many maps of social and health indicators in Baltimore still holds. The two regions in red in that last map make up the butterfly’s wings. Those CSAs are also the ones with the highest homicide rates.

You could say that it is in those eight CSAs where homicides are the most concentrated. These are known as spatial clusters. If we had significant “Low-High” or “High-Low” CSAs, they would be known as spatial outliers. Significant “Low-Low” CSAs would also be spatial clusters.

As I mentioned above, we can also do other analyses, some of them looking at the individual locations of the homicides, the dots in the first plot and the first map. You could generate statistics that tell us whether those dots are closer together to each other than what you would normally see if they were just tossed on the map randomly.

A full geostatistical analysis includes these analyses, and you can see an example of the whole thing if you look at my dissertation. You may want to include the Local Moran’s I value or some other term (I used average number of homicides in neighbors) in a regression analysis. Or you could use composite index to account for different factors.

The Big One?

Posted on March 2, 2020

In February 2009, I started to notice that the influenza season in Mexico was not ending like it usually did. I noticed that the number of people sick with influenza-like illness was continued to climb when it should have been going down. What ended up happening was the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic… My first pandemic as an epidemiologist and my second one as a human being.

I’m not that young anymore.

Those were some interesting times, for sure. We were working long hours at the health department, trying to come up with the best information to give to the policymakers. That was nothing compared to the healthcare providers and the laboratory staff who had to take care and test thousands and thousands of patients. And, of course, it doesn’t compare to the people who lost a loved one.

Still, the 2009 influenza pandemic was not as bad as it could have been. As it turned out, the H1N1 influenza virus was very virulent but not very pathogenic. While it went around the world in a matter of hours, it did not end up killing as many people as it could. It was no 1918.

So here I am in my third pandemic. This one — like the last one — is being billed as the “Big One” by people who don’t seem to remember history very well. In 2003, SARS seemed like the big one. In 2009, we know what happened then. In 2012, MERS seemed like the big one. Every time someone catches one of the many avian influenza viruses, they call it THE BIG ONE. But we keep on going.

No, I’m not minimizing the thousands of people who have died or are going to die from this novel coronavirus. I’m also not minimizing the disruptions it will cause. What I am saying is that we as a species will continue to move forward. Very few things can kill all 7.8 billion of us. And, if it does, we probably had it coming.

So let’s continue to wash our hands and be vigilant. Let’s not lose our minds and help this little virus hurt more people.

It’s not the big one. Not by a long shot.

On the Radio

Posted on February 20, 2020

I was asked to appear on a local radio show to talk about coronavirus a couple of weeks ago. The show was in Spanish, and it was a very quick discussion. If you speak Spanish, enjoy…

The Parent Ren, Part XII: Just Breathe

Posted on February 19, 2020

As Toddler Ren moves from the terrible twos and into the tyrannical threes, she has been learning that tantrums get the attention of the grown-ups. Combine that with her frustration that she hasn’t mastered English nor Spanish, and it makes for some moments that are trying, to say the least. I’m not going to lie to you: some of those times were very hard.

Lately, we have been doing a breathing technique. I take her in my arms and tell her to look at me. She raises those big sad eyes filled with fake tears (she really sells the suffering over not getting a chocolate bar) and looks at me. Then I tell her to take a deep breath with me. We take our deep breaths are things are better… For the both of us.

Sometimes, as parents, we forget to take a minute and understand what is going on with our children. We forget that they’ve only been on this planet for a short period of time and that their brains haven’t caught up with everything yet. Toddler Ren doesn’t understand all the nuances of language, and it is even harder for her to understand the nuances of Spanish when 99% of what she hears and speaks is English. Likewise, she doesn’t understand schedules and deadlines. She probably wonders why we don’t understand her, why can’t just do as she says.

As we have been practicing our breathing, I’ve come to understand how much I should have done that in my life. There were far too many times when I panicked — even for a few seconds — and acted without thinking, said things without thinking. I should have breathed — even for a few seconds — and let the prefrontal cortex do its thing.

But, hey, I have an opportunity here to make things right by teaching Toddler Ren that breathing is important, and that she should think and then act.

Right?

A Vaccine Fact Generator? Yes, Please!

Posted on January 18, 2020

So a friend of mine got the idea about creating a “fact generator” for vaccine facts. The idea was to click on a button on a website, have a random fact about vaccines appear, and then let people share that fact via Twitter. Recently, an online course for people learning Javascript led students through how to build a “random quote generator.” I figured I could take the code and modify it.

First, I had to find the right code. Luckily, I ran into a page by “Jay,” where he created a random quote generator. I contacted Jay via Twitter and asked for his permission to use his code, and he agreed. So I modified it a little here and there, and now we have the Vaccine Fact Generator.

It uses some HTML and some Javascript brought together by Paper CSS to create a web application where the user clicks on a button and a random fact appears. Then, as I wrote above, they can click on another button and send that fact to the Twitterverse.

There are still a couple of things I want to do before I can call it v1.0: First, I want the links in the fact box to be clickable, and, second, I want the ability to also share to Facebook. Actually, either of those would be good enough for me to call it v1.0. Until then, I’ll keep incrementally adding facts and tweaking some settings.