My Obsolete MacBook Pro

Posted on July 19, 2020 3 Comments

“You know,” I said to my wife, “I think I’m going to buy that new MacBook.” We were driving down the road to go grab something to eat. It was the summer of 2012. I was still working at the Maryland Department of Health, but I was picking up more and more side gigs writing. I wanted to have something a little more “robust” than the MacBook Air I had at the time. As much as I loved that computer for its portability, it had a very rough time keeping up with all the different programs that I used to edit documents, images and video.

“Who are you kidding,” my wife replied. “You already bought the son of a bitch.” She was right. I already had.

It wasn’t a cheap computer to buy, but I figured that I could write it off as a business expense since I was going to use it a lot for all the writing/editing gigs. And I did. It proved itself to be a good companion for those adventures, and then some. It traveled with me to Colombia and Puerto Rico. When dad got sick with colon cancer, it came along with me to Mexico. I wrote much of my dissertation on it when I traveled to and fro.

I have another MacBook Pro that is newer and more powerful, but it is strictly for work I do at home. Anything else I do on the go — and is not related to work at the health department — gets done on the 2012 MacBook Pro with Retina Display… A computer that just got designated as “obsolete” by Apple. I’m planning to keep it going as long as I can, hopefully until 2022. A ten-year-old MacBook? Who has heard of such a thing?

I mean, I have no doubt that someone has a running MacBook from 2006. It’s just kind of neat that this thing is now at eight years of age and runs modern software on it no problem. It can edit a video, albeit slowly. It can have several programs running simultaneously, albeit slowly. And it can take a beating… This aluminum construction is quite durable.

So, here’s to all the old things — and people — who have been deemed obsolete and the people who use them and make them contributors to the work that needs to be done every day. Here’s to the toys you bought to help you get your work done by making it easier and more enjoyable. And here’s to the women in our lives who can read us like an open book and know when we’ve already spent a good amount of cash on something. (How does that work?)

Most of all, here’s to midnight rants on your personal blog, illuminated only by the light of your retina display on a quiet night while the loves of your life sleep soundly.

Header image by Tianyi Ma on UnsplashWhat You Need to Know About COVID-19 Right Now (mid-July 2020 Edition)

Posted on July 16, 2020 3 Comments

The Coronavirus Pandemic continues around the world and in the United States, with states in the American South and Southwest right now reporting the highest numbers of cases. While states in the North, Midwest and Northwest United States don’t have as many cases, cases there are still simmering, waiting for the reopening plans to go sideways and allow the virus to make a comeback.

Meanwhile, the entire country is locked in yet another social and political battle over school re-openings. Some school systems want to continue online learning. Others want full, in-classroom learning. Others want a mix of both types. And the people in the White House want a full return to classes, with seemingly nothing in between.

Good stuff.

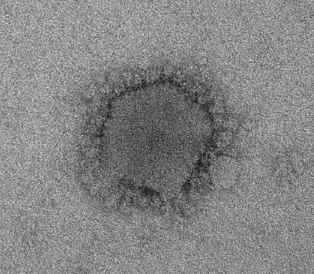

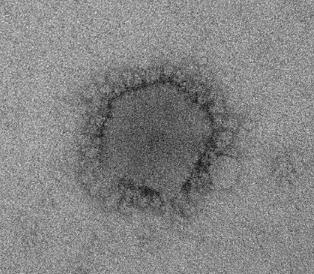

The Coronavirus Continues to Be a Virus

One thing that has not changed about the coronavirus is that it is still a virus. It is still in a lipid envelope that can be disrupted through soap or alcohol sanitizers. Hand washing is still highly effective at preventing infection because hand washing washes away and kills the virus, reducing the chances that you contract it by bringing it into your nose, mouth or eyes through contaminated hands.

Contrary to what conspiracy theorists want you to believe, the virus is not some result of an experiment gone awry. It is no one’s Frankenstein monster. Based on the genetic analysis of the virus, it came about through natural processes. That said, many of those processes could have been avoided. The increased encroachment of humans into wild areas for housing, food and raw materials is a big concern. It causes what we call “spillover” events.

The virus is still relatively heavy and will not travel long distances on its own. This is why we continue to recommend social distancing of at least six feet (two meters). Because coughing, sneezing, yelling and singing can launch the virus further as it grabs on to your spit, mucus or cells, we also recommend cloth face masks. While they will not 100% protect you from infection, they will prevent you from launching the virus is you’re one of the many people who carry the virus asymptomatically.

Speaking of Symptoms

At the beginning of the pandemic, there were three symptoms we were focusing on: fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Since then, we’ve learned that there are a variety of other presentations of a coronavirus infection (COVID-19 is the disease caused by the infection). The definition of a case has changed to include more symptoms: body aches, chills, loss of smell, loss of taste, sore throat and headache. Of course, these symptoms alone don’t guarantee that you’re infected with the virus, so you need to see a healthcare provider if you or someone in close contact with you has had these symptoms.

Only a lab test can diagnose the infection.

Speaking of Lab Tests

There are now more lab tests available not only in the number of tests but in the types of tests. Initially, there were only PCR (polymerase chain reaction) tests available to detect the virus RNA. Now, we have tests to detect the virus antigens (bits of protein or fat or sugar) on the virus surface. We also have tests for antibodies against the virus. Soon, there will be tests for immune markers other than antibodies that our bodies make against the virus.

We need to take all of these tests with a grain of salt, however. The PCR is still the “gold standard,” the test that if positive means you are infected and if negative means that you are likely not. If that test is positive, however, we do not know how infectious you are, or if you’re likely to develop the symptoms and complications — and now sequelae — of the infection. What we do know is that you need to go into isolation for at least ten days while your close contacts go into quarantine for fourteen days.

The other laboratory tests are still not quite there with regards to their sensitivity and specificity — the two measures by which a healthcare provider or public health practitioner can be certain that a positive is a true positive or a negative is a true negative. They’re either not there because their technology is new, or because — as is the case with antibody testing — the virus is new. There is some good evidence that antibody tests might be picking up antibodies against the other human coronaviruses and not this human novel one, leading to false-positive results.

But We Really Don’t Need Masks, Right?

For the life of me, I can’t figure out why the allergic reaction to wearing masks. Some people say it is a form of tyranny, an overreach of government toward its citizens. Others believe that this pandemic is not happening, so wearing a mask in public would be an acceptance on their part that it is happening. Then there are those with, seemingly, a form of oppositional defiant disorder who don’t want to just because.

Whatever the case is, we need to understand that they are in the minority. Yes, they threaten the rest of us who decide to follow public health recommendations and wear masks, but we shouldn’t feel like we — the ones who follow reasonable recommendations — are the weird ones. You — yes, you — who follows recommendations, gets your children vaccinated, washes your hands… You’re the “normal” ones (for lack of a better term). We outnumber them.

There is no vaccine against the Dunning-Kruger Syndrome.

Speaking of a Vaccine

A vaccine against this coronavirus is still months away. Even with recent news that participants in a trial made a lot of antibodies after being vaccinated, there is no guarantee that those antibodies are specific enough to grant immunity… Or that they will be around long enough to allow us to reach herd immunity.

I’m not pessimistic about this, actually. I’m quite optimistic that we will have a good vaccine in 2021. It’s just that this rush to publish results by press release rather than peer review is going to get someone hurt. Not only might we end up with a Dengue vaccine-type of fiasco, but we could end up with people plunging a lot of money into a company selling vaporware when it comes to a vaccine.

Still, if you’re curious and want to track the progress of vaccine studies, check out this tool from The New York Times.

In Conclusion

So this is where we are right now. Cases on the rise in the South and the Southwest; the virus is still a virus that hygiene, cloth fase masks, and social distancing can defeat; a vaccine is months away, but it should be here in 2021; and you are not in the minority when you see so much attention being given to people who won’t listen to reason.

Let me know if you have any questions.

The Parent Ren, Part XIII: Passing on Some Knowledge

Posted on July 16, 2020 1 Comment

The pandemic has been very weird. On the one hand, you have a pandemic — something that, by definition is worldwide and happening concurrently — but then we’re seeing its effects in spots around the country instead of all over simultaneously. This is not a bad thing, per se. I’d rather we buy some time here and there to counter the effects of the pandemic than to have it strike all at once and take out a sizeable proportion of the population.

While all of that madness has been happening, we have struggled to keep the Toddler Ren learning. Like the toddler that she is, she has many questions. The whole world is brand new to her, so she wants to understand it as good as she can from the limited point of view she has as a toddler and as someone whose brain is still under construction.

For this, we were lucky enough to be able to afford a babysitter while the daycare was closed. There was always someone with her at home, and the babysitter did a great job looking after her. But I always wondered if Toddler Ren was missing out on something by not being in daycare. As it turns out, she wasn’t. A month after the daycare opened again, we took her back, and it was as if she never left.

This all got me thinking of how we pass down knowledge from one generation to the next. Of course, there is formal education, and we expect schools to teach our children a certain set of skills. But what about all that other stuff we learn from our parents? How does that get passed on effectively?

Yes, there is the whole “monkey see, monkey do” stuff. She certainly tries to imitate everything that we do around her. She wants to be like a grown-up, but doesn’t quite achieve what we can achieve because she’s tiny and inexperienced. In due time, and with plenty of practice, she’ll probably be able to do everything we do — and do it better. But what about all the other stuff we learn?

I was telling my wife the other day about how I was basically raised by television. When mom worked and there was no one to watch me after school, I’d go home and watch television while working on my homework. I knew that I would get to play outside with my friends if I got my homework done by the time mom got home. All that television-watching taught me a lot of lessons in morality.

I got to see how one small little lie snowballed into bigger lies and then into trouble for the protagonists. There were all those stories of crime not paying, or where the bad guy got their comeuppance. All of those stories were repeated over and over in almost all episodes of cartoons and television shows. Even shows like Bugs Bunny or Tom & Jerry had some morality tale woven into them.

Old stories I learned about in my Spanish and English literature classes were the same, for the most part. They taught the reader something about being honest, loyal and true to oneself. The bad guys never won. Love overcame everything. Those were simpler times.

Certainly, mom and dad — having been divorced a few years into their marriage — didn’t personally teach me about marriage and devotion to my wife. Oh, but they did teach me about the perils of getting married too soon and for the wrong reasons… And what happens when you don’t have respect for the other person involved in the equation that gives rise to your child.

So, yeah, I guess I learned some stuff.

As we continue to have this debate on what to do about schools reopening, we need to recognize that schools also play a big role in what our kids learn. Many of the life lessons I carry with me today are because of the people who dedicated their lives to teaching. I hope that whatever plan we come up with, it doesn’t end up hurting teachers. Similarly, I hope students don’t end up losing too many lessons.

For the time being, I’ve taken to writing Toddler Ren a series of essays on life and living. It will be awhile before she reads them, of course. Meanwhile, she’s going to be mirroring a lot of what we do, so we need to be good role models. And, by golly, I better make sure to live up to all that I’ve written…

Someone Yelled Something While I Was Out Jogging Today…

Posted on July 13, 2020 3 Comments

As I went out for a jog this evening, I ran on a trail that runs behind several houses in our development. It’s a nice trail, with lots of hills and valleys to really work up a sweat and build up some stamina. It has trees and grass on either side, so there’s some shade should one choose to run in this summer heat.

By now, you’ve no doubt heard of all the instances where people call the police on Black or Brown people for an assortment of frivolous reasons. In one instance, a man was painting the front of his house when a woman approached him and asked him if he lived there. It would be hilarious if it wasn’t so sad.

As I was running jogging today, I heard a man yell out from the back porch toward me. “Get out of here!” he yelled. “Go on! Get the hell out of here!” Almost immediately, I thought to myself: Well, this is it. In a few microseconds, my brain began to play out all the possible permutations of what was about to happen. The guy would call the cops on me, a big Mexican guy running behind his house, and there would be some explaining. I’d have to not even pretend to reach for anything around my waist. I’d have to speak English well, eliminating my accent as much as I could.

These images came to my mind:

In another instance, a woman calls 911 on a man doing some birdwatching, telling the dispatcher that she is being attacked by a Black man.

In New Jersey, a White woman calls the police because her Black neighbors are doing some sort of landscaping on their yard.

This woman calls the police because a Black little girl is selling water outside her apartment.

In North Carolina, a man asks a Black woman for her ID when she wanted to go to her neighborhood pool.

You get the idea.

Seconds after the man yelled, I thought to myself: No, screw that. I was not going to stand for it. No one was going to tell me in my neighborhood where I could and could not run on public property. We worked too hard for too long to buy our home for some random guy who doesn’t know me to yell at me like that.

I turned around and spread my arms out. “What?” I yelled back at the guy. He was looking somewhere else and then looked at me. He then looked back at where he was looking previously, and then back at me. It was then that we both understood what had just happened…

A deer went running out of some shrubs in his backyard, jumping a fence and then running away from me on the trail. We both looked at it run away and then looked at each other. He nodded and smiled and waved at me, and I waved back. Then I started jogging away, thinking that these are some crazy times that have us all on edge.

It was a big deer, though; and she didn’t look healthy.

It just so happened that I was listening to Radiolab, and it was an episode about the history of the Confederate Battle Flag embedded in the Mississippi State Flag. It was tough to listen to it, especially all the racist chants and accusations toward people who only wanted to exist and be seen as human beings. So, yeah, I was a little more on edge because of that. But think of what all these craziness has brought.

I was ready to go to war with one of my neighbors — albeit not literally — because I was convinced that he had joined the chorus of bigots who demand of People of Color a reason for their existence. It was a harmless mistake on my part, but can you imagine if I reply to him with an obscenity instead of just a simple “What?”

In that sense, I hope that I have the wisdom, when confronted with real and not mistaken hate, to be wise in my response and not get so emotional or so caught up in the moment. At the end of the day, people on both sides of the equation of anger, fear and hate have something to lose. And I have much, much, much to lose.

And so do we all…

Header image by Francesco Gallarotti on UnsplashThe Things You Need to Think About Before You Reopen Schools

Posted on July 10, 2020 3 Comments

I’d like to start off this blog post by telling you that I am in no way advocating for or against reopening schools. This is currently a hot-button issue, and many policymakers are scratching their heads on how to do school reopening correctly. I am also not telling any one person or group how schools should reopen. I just want to tell you a few things that you need to know as we move toward that moment when they do reopen.

In 2009, when the H1N1 influenza pandemic happened, we were lucky because we had the tests for the virus rather quickly. Even if we couldn’t identify the H1N1 novel influenza virus itself, PCR analyzers could tell us that they detected an influenza virus but couldn’t tell what subtype it was. With coronavirus, things are different. PCR analyzers spat out a negative-to-all-known-viruses result early in the epidemic, so it was hard to identify cases.

Now, we are going into a phase of unintended consequences of laboratory testing. It’s not that we have enough tests; we probably don’t. It’s that we have many different types of tests. There are the PCR tests that detect the virus’ genetic material. There are the rapid antigen tests that detect the virus’ antigens (those little bits of protein on the virus surface). There are antibody tests that require blood. There are viral cultures that grow the virus. Currently, only the PCR test is good enough to be the “gold standard,” but it is not available everywhere.

So we need to be cognizant of the laboratory testing that children will go through before, during and after school is back in session. Is it the gold standard or something else? Is it accurate? Is it sensitive, thus giving us good confidence that a positive is positive? Is it specific, thus giving us good confidence that a negative is a negative? Is it easy to do? Is it cheap enough that children of all socioeconomic strata will be able to have access to it?

Another thing that helped us in 2009 was that a vaccine was available in less than one year. In fact, it was available the same year that the virus made its appearance. This is because the technique for making influenza vaccines was already available. All that vaccine manufacturers had to do was replace one strain in the vaccine with the novel pandemic one. That is not the case today. Today, there are many laboratories around the world working on a vaccine that will be brand new.

So we need to be cognizant that a small proportion of the population will have been exposed to the virus if the schools open in September. This means that a huge proportion of the population will not have been exposed, and, thus, there will be many susceptible students congregating in schools. Even if they have been exposed and have antibodies, the jury is still out on whether they are immune or susceptible after an initial infection. Both school officials and public health officials will need to have a sense of what level of immunity there exists to understand any possible school-based epidemics.

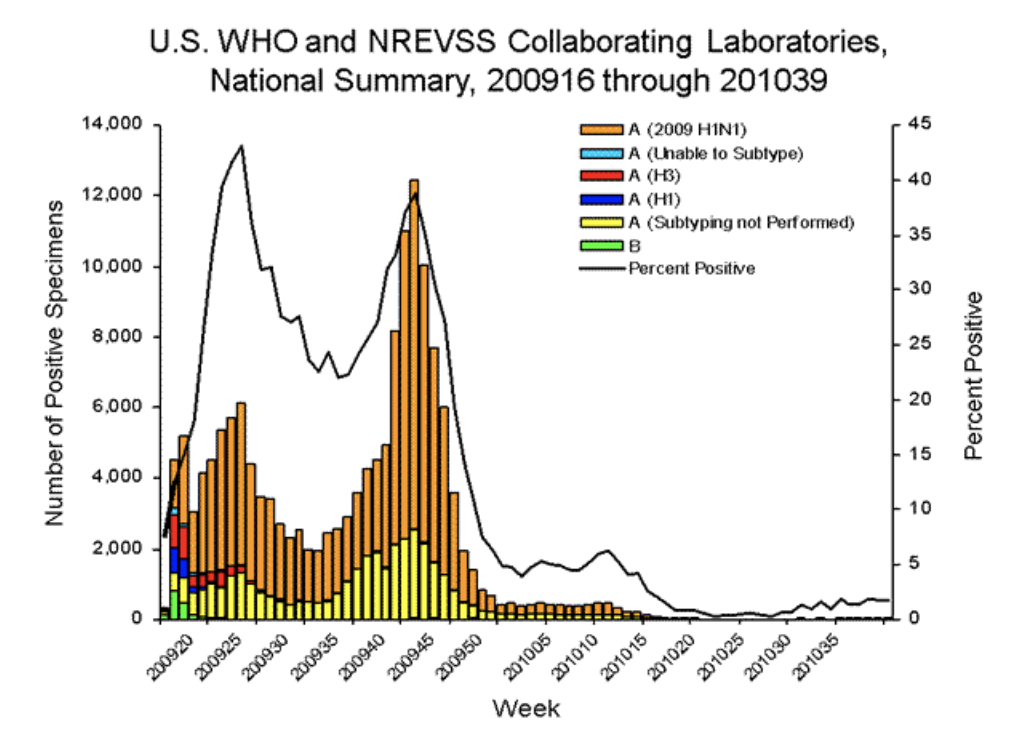

Then there is what happened in 2009 when the children did return to school. Look at this graph from CDC:

As you can see, there was the initial wave of H1N1 influenza in week 20 (May) of 2009. Then the massive wave hit around week 35 (September). If you were to look at the second wave on a state-by-state basis, you would have seen it happen first in the South, where states like Georgia started school in late August. The wave then marched its way up the Eastern Seaboard and then toward the Midwest and the western half of the country. It lasted well into December, and it was the time when the most people died from it.

Of course, many people who know a lot about viruses and epidemiology will fight me on this and say that influenza is one thing and coronavirus is another. This is, of course, true. But they both are viruses where hand hygiene and clustering of people are critical to its transmission. So I’m not convinced that the coronavirus will behave differently when schools go back in session. Not only that, but the level of asymptomatic people who are infected and still pass it on is a big, huge concern that we need to be aware about.

You can also kind of see the effect of the fall vaccine campaign in the graph above. Notice how the second peak collapses in a matter of about four weeks while the one in May to July seemed to last for about eight weeks after that peak. And then see how it all ends by week 15 of 2010, with virtually nothing after that. In 2010 to 2011, we had an “average” flu season in which H3N2 influenza prevailed.

How do we detect asymptomatic infections? What kind of testing scheme do we need to put in place? And, going back to my previous point about testing, which tests are admissible to detect cases and which ones are not? Which ones do we trust?

Then there are the issues of the inequities and inequalities that the pandemic has brought out of the darkness. Latinos and Blacks are more likely to catch the disease or be part of localized epidemics. Latinos may not be as likely to die (as they are relatively younger as a population), but Blacks are (as they are more likely to have serious comorbidities)… All when compared to Whites and Asians of similar socioeconomic status. Then, when it comes to socioeconomic status, poorer people are more likely to get sick and be hospitalized and die from coronavirus than wealthier folks.

What does this mean for poor schools and poor children going to those schools? What does it mean for wealthy schools? You get the idea…

At the end of the day the decision on opening schools is going to be a policy one decried or supported by politicians, parents, teachers and school administrators. Sure, it will have some input by public health, but — as we have seen lately — many public health recommendations can be overridden by governors and mayors and others. Even individuals can choose to ignore public health recommendations.

But I would be irresponsible to the profession if I didn’t point out all these things… And others that are a little more complex than what can be hashed out in a blog post. I just hope we all have the time to hash it out.

I really do.

Header image by Feliphe Schiarolli on UnsplashTwenty Years Since…

Posted on July 9, 2020 3 Comments

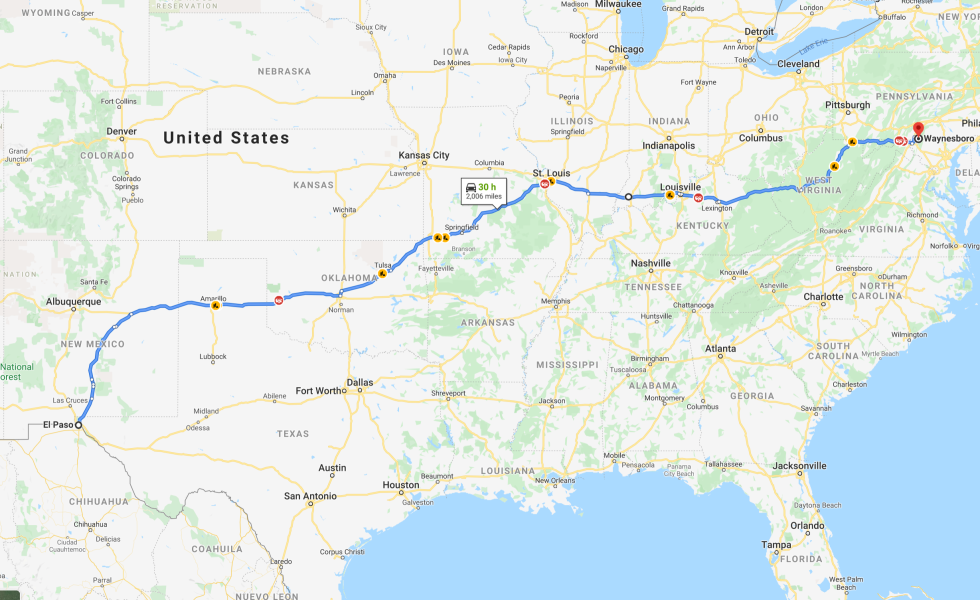

Most if not all of my friends and family looked at me like I was a salamander on a salad when I told them that I wanted to move out to the East Coast after college. I had never been east of the Mississippi. The farthest from the El Paso region that I had gone was Mexico City, and I had no one waiting for me out east. But, in the tradition of my father and his father before him, I was going to venture out into the world… I was going to take a leap of faith.

It’s late in the afternoon of July 4th. My dad and I have packed all of my belongings into my Suzuki Samurai and his Geo Tracker, two tiny cars with great fuel mileage. We plotted our route on an old road atlas that dad bought from Walmart a few years back when he set out to work in the oil refineries in the South. It was a big old book full of notes and marks where that had annotated his stops and his expenses. He closed it and tossed it to me and told me to lead the day. I said good-bye to my grandmother, and we were on our way.

As we drove north out of El Paso on Route 54 toward Alamogordo, I looked back on the city and saw the Independence Day fireworks going up at different points. The sun had set and the coming night would be long as we had decided to drive through the night and stop at a rest stop near Tucumcari, New Mexico. We would sleep there and then start driving east to Amarillo, Texas, and then on toward Oklahoma City on I-40.

A month earlier, I had flown into Baltimore from El Paso and was picked up by “Dade,” a head hunter from a firm helping the little hospital in Pennsylvania find a medical technologist. I had loaded my resumé to Monster.com and had a few phone interviews before Dade’s company (The Bridge Group) found me and asked me to fly up for an interview.

I didn’t exactly have money to fly to Baltimore, but my oldest cousin — someone who has been on my side literally all my life — gave me some cash and told me to get out of El Paso for my own good. I arrived in Baltimore, and Dade drove me east to Frederick, then north to Thurmont, then up between the “mountains” to Waynesboro. We talked about the job and the area where the hospital was located. All the while, I was impressed at how green everything was, very different from the Chihuahua desert where I grew up.

As dad and I rolled out of Oklahoma and into Missouri on I-44, we had stopped to eat at a diner on the side of the road and had a good chat. We talked about the new job that awaited me and my plans for the future. He asked me about the girl in El Paso who I had said good-bye to over the phone while we continued to pack things up. I explained to him how we were just friends, how I wanted more — obviously — but she never seemed to make up her mind on what she wanted. When he asked me about any more schooling, I told him that the college degree was enough for me and that all I wanted to do now was make money. We stayed at a motel in Joplin that night, July 5th.

The lab manager at Waynesboro picked me up at the hotel where Dade dropped me off and took me on a tour of the little town. He told me all about the Civil War history that happened there. Being so close to Gettysburg, a lot had happened in that area. We then went to the hospital and had a chat about the job. Little did I know that a couple of anecdotes Ray told me and engaged me on were actually tests to see how much I knew. By the end of the interview, he offered me the job.

From Joplin, we made our way to St. Louis. We stopped once in a while to use the bathroom, eat, chat. It was a nice drive with no bad weather. With luck, we’d be in Waynesboro by the 9th, giving me a few days to find an apartment and settle in before having to work. That was the thing that annoyed dad the most: my lack of planning on where to stay. But I had a few extra hundred dollars from Joe. If push came to shove, we’d stay at a hotel a few days.

As I left Baltimore to go back to El Paso, I had in my hands a folder full of information about the new job. To me, the wage of $18 an hour seemed like a ton of money. It was certainly more than the minimum wage I was earning at the mall in El Paso. But I also had worries that things were going to change. I was going to leave a lot of people behind, people I cared about. But something — perhaps the spirit of adventure — was calling me to leave and go write my own story. And so, I got to El Paso and wrapped everything up that needed to be finalized and made plans with dad to drive up to Pennsylvania. I said goodbye to friends old and new. I said goodbye to relatives good and bad.

From St. Louis, we decided to go east to Louisville and then Lexington, Kentucky. I remember looking out the window of my car and seeing that the grass was different. I wondered if it was the “blue grass” that they always mentioned about the South, or if it was just my eyes playing a trick on me. By July 7th, we were in West Virginia, so we decided to press on toward Waynesboro. We arrived there that day and slept in our cars in a park on the late morning before getting a hotel room for the night.

As we drove around town to get a feel for it, we saw a Mexican restaurant, so we went in for some food. The story of that restaurant, and the waitress who became a nurse, is best left for another day. But I will tell you that the food there was not that authentic… The buñuelos were not buñuelos.

Dad stayed for a couple of weeks before he headed down to Georgia for work. In that time, I settled in and started the job at the hospital lab. Days turned into weeks, and weeks turned into months. Months then turned into years. Those years brought with them many adventures. There were tons of good times and tons of bad times. All the while, I continued to learn and grown and learn from my mistakes and those of others.

The original version of this blog started in 2004, when I was still there, and I can see a very young and very naive me in all of those blog posts. In some of them, I’m angry that things don’t work the way I thought they should. In others, I’m happy. Just like any other life, this one has been full of challenges in rewards in the last 20 years, and I look forward to what the next 20 years will have to offer.

The Abuse You’re Going to Have to Take

Posted on July 2, 2020 2 Comments

It’s been a weird pandemic. From day one of the response, I was asked to manage several very young and very bright public health workers for several jobs. Later on, I was promoted to managing other public health workers. Through it all, I’ve tried to follow one rule: Always be on the side of my people.

One thing that I have not tolerated is any kind of abuse of the people I manage, internal or external. For example, early in the response, someone who had traveled to an area with COVID-19 was asked to stay home in quarantine on the chance that they picked up the virus and brought it back with them. Part of the deal was that they signed a quarantine agreement to stay home, check for symptoms and notify us immediately if they did develop symptoms. One person send the agreement back by email, changing the title of the document to something like “giving_up_my_rights.pdf,” or some such.

They thought it was funny, but I didn’t. On top of all the other abuse from people who don’t like the government telling them what to do, this person took it one step further. So I had a chat with them. In fact, I’ve had many chats with many people since this whole thing started, and few of them have been non-confrontational.

The worst one yet came this week when a “concerned citizen” asked for clarification on some numbers we were reported. As it turns out, they didn’t want clarification. The call ended up being over 45 minutes long, and this person did nothing but launch one accusation after another… Even suggesting that I was “peddling” to President Trump.

By now, you’ve probably heard of all the public health officials (many of them women and/or people of color) who have resigned or made to quit, or fired, because of the political divisions that exist in this country with regards to the pandemic. I get it. I would not want to be in the position that so many of them have been put into when all they were doing was their job of protecting the public’s health.

What bothers me the most is that their bosses, the people who should have been on their side, did nothing to stand in the way of the abuse that the people on their team were taking. That’s not leadership nor management… That’s just dereliction of duty. Lucky for me, my bosses are very supportive, and I’m about 78% sure that they would step in and help me if I were to be harassed like others have across the country.

The thing is… There are many other situations in which people I care about are harassed and abused, and there is little that I can do to stop it. Some people have to fight their own battles, learn from them and become good “warriors” for the battles yet to come. Still, I wish that I could do more because — to be honest — there is a lot of injustice in the world that needs correcting.

For now, we keep moving along in the pandemic, taking all the hits and keeping keeping on.

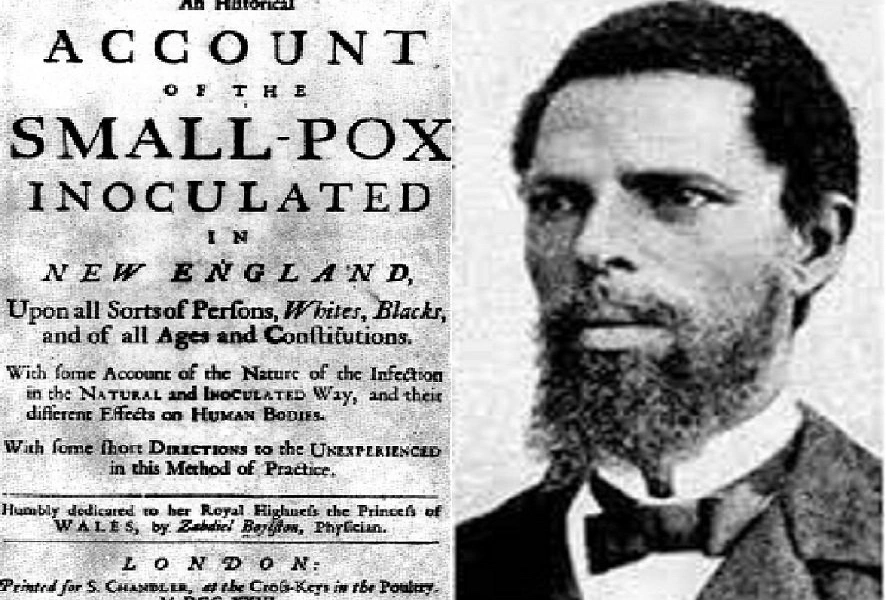

Operation Onesimus

Posted on April 13, 2020

After hearing that the Spanish government had named their response to the COVID-19 pandemic “Operación Balmis” after the Balmis Expedition of the early 1800s, I decided that my own personal response to the pandemic had to have its own name. The Balmis expedition was an expedition headed by Javier Balmis, the royal surgeon to the King of Spain in the early 1800s. As Jenner’s discovery of the smallpox vaccine became widely known, the King decided that his subjects in the Americas and in the Philippines were going to be free from the scourge of smallpox. He read Jenner’s papers and those of a French physician validating Jenner’s findings. So he entrusted Dr. Balmis to head the expedition and bring the vaccine to what is now Latin America and the Caribbean.

After a long deliberation on what to name my personal efforts in the Pandemic, I decided to name it Operation Onesimus. Onesimus was an African slave who was forcefully brought to the American Colonies in the early 1700s. At that time, there was no vaccine against smallpox. The disease just came around time after time and would take the lives of hundreds or even thousands of people. There was not much beyond social distancing that the people could do. By the time they realized they had an epidemic on their hands, many people had been exposed and would be sick. Many of them would die.

Onesimus was bought by Cotton Mather, a clergyman from the Massachusetts Colony. Reverend Mather, if you remember, had been involved in the Salem Witch Trials. As one epidemic of smallpox went through Boston and the countryside near it, Mather noticed that Onesimus was immune to the disease. He also notices that Onesimus was bright, seemingly education. Mather asked Onesimus about his immunity, and Onesimus pointed to his arm.

For centuries, people who wanted to be immune to smallpox would ask to be variolated. Variolation is the process by which the smallpox disease (variola) would be given to people in a controlled manner and under the supervision of a physician. The process usually included taking some of the pus from a person with smallpox and injecting it into the arm of a healthy person. The person would then develop a milder form of smallpox and then recover and be immune. Some people would get the full-blown disease, especially since there was no knowledge of how much pus with smallpox was too much. (We know now of things such as viral dose.)

Onesimus had been variolated when he lived in Africa. It is believed that the Arab traders who ventured into the sub-Saharan part of the continent brought the practice with them. When people found out that variolation prevented smallpox, they went along with it. Onesimus had been one such person, and that is why he survived so many smallpox epidemics in Massachusetts. He told all this to Mather, and Mather consulted with physician friends about it. After much deliberation, Mather and his physician friend decided to give it a try. After successfully receiving the variolation procedure, Mather and his family — and the family of the physician who went along with the plan — were spared from yet another wave of smallpox that went through the colonies.

This was not without consequences for Mather, though. What is perhaps the first anti-vaccine group formed around him and even firebombed his house. They claimed that he had given in to “African witchcraft” by taking the advice of a slave. Mather didn’t relent. He recommended the practice to other people in the colonies and in the British Empire. By the time the Americans decided to revolt, variolation proved to be key to defeating the British… But that is for some other time.

I decided to call my efforts “Operation Onesimus” because I decided to use the knowledge and wisdom of others throughout the generations to guide what I was doing. From John Snow’s crazy idea to map cases of cholera to understand its spread to my Hopkins professors’ lessons on epidemiology and public health, I was going to use everything and anything to try to make a dent in what is going on. And it would not matter to me if the naysayers were incredulous of my efforts. I was going to use all that to do well and try very hard to save my own corner of the universe, even if I didn’t do it.

As the pandemic has evolved, however, I’ve decided to change the name of my efforts to a new name… But that is for a later post at a later time. For now, it’s time for sleep, because sleep is at a premium right now.

Stay safe out there… We’ll get through this.